I was saddened to learn this weekend that Pam Cleaver has died. Pam was a regular reader of Wenlock and a frequent commenter. A while ago she asked whether I would be prepared to take a look at her novel, The Reluctant Governess, and see whether or not its heroine was in need of a slap. I never got round to doing it before she died, but now I have.

Belinda Farrington (The Reluctant Governess by Pamela Cleaver)

Our first impression of Miss Farrington is that she is a very sensible young woman. Orphaned, and with the fiancé that she hardly knew killed in the war, all that she really wants to do is become a romantic novelist. However she recognises that this is a remarkably foolish ambition that nobody in their right mind would consider when other options, such as marrying for money, or even becoming a governess, are readily available. She therefore abandons this idea.

Unfortunately this seems to be her last sensible move.

Anyone who has read any Heyer would know that Harrogate would be the perfect place to find either a rich husband or a post as a governess. The town is dripping with cousins of peers and crawling with every type of mushroom. However for reasons that we never really understand, Belinda decides to leave Harrogate and try her luck in York, whose Regency credentials do not go much further than an association with Dick Turpin. It is hardly surprising that Belinda finds rich widowers and governorial vacancies few and far between. Before she takes the sensible step of giving up and going back to Harrogate, however, an opening appears, and Belinda dives right in.

What Belinda fails to spot is that the post that she has accepted is in Suffolk.

There are only a few places to be found in Regency England that have even the smallest amount of ton. London of course, and Brighton, Bath and Harrogate. Leicestershire contains nothing but hunting boxes, and Newark is no more than a place to change horses. Hampshire is the preserve of Captain Swing. That's about it. Suffolk certainly had no ton until it was brought into fashion some 130 years later, and even then it was basically just a place for children in boats. The only explanation I can come up with for Belinda's decision is that she was aiming to get a jump on Mr Ransome.

In the absence of ton, the people of Suffolk have to make their own entertainment, and it seems that they have gone in for an odd little game called "Who is the Master-smuggler?" The rules are complex, falling somewhere between Cluedo and Mornington Crescent, and involve china cats, windmills and the occasional lynching. The object of the game appears to be to collect various items - brandy for the Parson, tobacco for the Clerk, laces for a lady, and so on. The winner perhaps being the first person to collect a complete Kipling poem, providing that the Riding Officer doesn't catch them first. In most respects the Suffolk game is exactly as played in Cornwall, Devon, even Norfolk, but what Belinda seems not to have spotted is that in Suffolk thay have introduced an extra rule: if you accuse somebody of being the Master-smuggler without any evidence they can propose marriage to you, at which point they get another turn.

So poor Miss Carrington spends her time trying to turn the turbulent Sheldon family into Swallows and Amazons, while sending accusations flying and failing to understand why every eligible young man in the area is popping up and proposing marriage. With her charges unconvinced of the virtues of the Ransome oeuvre, this situation might have gone on for a considerable while, were it not for one of the Sheldons making a tactical error (possibly while attempting to get points for something torn with the lining wet and warm) and getting caught by the Riding Officer. At this point the game is declared officially over, and it is discovered that rather than real brandy and tobacco, everybody has just been smuggling pecadilloes after all.

It would spoil the story to give away the full details of the ending, but suffice it to say that if this is the behaviour of a reluctant governess, just think what an enthusiastic one might have gotten up to.

Wednesday, 30 November 2005

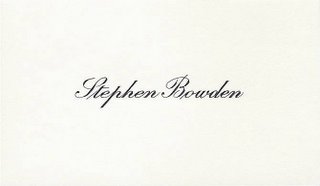

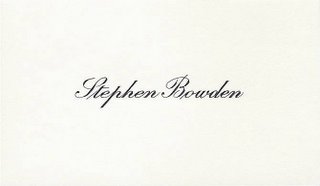

I have always envied Max Ravenscar's calling card, as described by Georgette Heyer in Faro's Daughter. It was a plain card that just bore the words "Max Ravenscar, Esq". At the time - the late 18th century - such a card would have been hand engraved and printed on cream board. I was pleased to find that Mount Street Printers and Stationers could make cards of this sort, so last time I was in London I ordered some, and I picked them up on Monday. Mount Street have done me proud:

If you click on the image you will see a magnified version which shows clearly that it has been hand-engraved. What you cannot tell from the scan is that the print is slightly raised - the sign of proper engraving. I decided to go without the "Esq"; I understand that in some circles it is taken as indicating that one is a lawyer, which I am not.

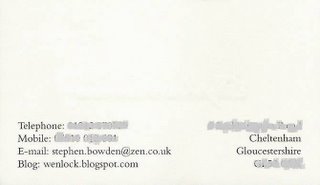

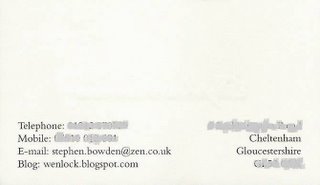

In Max Ravenscar's day everybody would have known how to find him, so an address would have been unnecessary, and of course, with the exception of Bertrand Saint-Vire in Devil's Cub, nobody in Heyer's books had a mobile, or indeed any other sort of telephone. Even I must occasionally accept that times have changed, so the back of the card carries all the necessary details.

Oscar Wilde wrote that "three addresses always inspire confidence, even in tradesmen", so in this case we have a street address, an e-mail address and a url - although you already know the last of these.

If you click on the image you will see a magnified version which shows clearly that it has been hand-engraved. What you cannot tell from the scan is that the print is slightly raised - the sign of proper engraving. I decided to go without the "Esq"; I understand that in some circles it is taken as indicating that one is a lawyer, which I am not.

In Max Ravenscar's day everybody would have known how to find him, so an address would have been unnecessary, and of course, with the exception of Bertrand Saint-Vire in Devil's Cub, nobody in Heyer's books had a mobile, or indeed any other sort of telephone. Even I must occasionally accept that times have changed, so the back of the card carries all the necessary details.

Oscar Wilde wrote that "three addresses always inspire confidence, even in tradesmen", so in this case we have a street address, an e-mail address and a url - although you already know the last of these.

Tuesday, 29 November 2005

Last night saw a reunion of the RNA University Challenge Team for the 2005 PEN Media-Biz Quiz. The team (Catherine Jones, Anne Ashurst, Jenny Haddon and I) was joined by Judy Astley, Katie Fforde, Joanne Harris, Jill Mansell, Evelyn Ryle and Roger Sanderson to form a table of ten for an evening of dining, drinking and answering fiendish questions for a good cause.

I had a cunning plan for the evening. We would do spectacularly well in the early rounds, thus raising our profile and ensuring that the hordes of publishers and agents present would flock to see us. This plan worked brilliantly all through the pre-dinner drinks (it's nice when an event gets sponsored by Dom Perignon) and was still on track as we sat down to our appetising appetisers, and then, as the first set of questions ("The Sports Pages") were read out, I realised that it wasn't going to be quite that easy. We did OK - we knew that Claudio had suggested that Benedict's beard had been used to stuff tennis balls, and that Rabbit Angstrom had played a game of basketball at the beginning of Rabbit Run (I never made it past chapter one, but luckily that was where this event took place), and we knew that Alice played croquet with a flamingo. We were less good at knowing what greasy ball had flown past James Joyce's face in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and couldn't remember who had played against the Dingley Dellers in the criket match in The Pickwick Papers. OK was never going to be enough in such company.

We did even worse in the second round ("Courtroom Sketch") and by the end of Round 3 ("Talk of the Town") it looked as if we were in severe danger of coming bottom out of the 37 tables taking part. So much for stunning the assembled cream of the literary scene with our intellect. Luckily the rest of the dinner was served at this point so we could concentrate on other things.

The fourth round ("Juke Box Jury") had yet more fiendish questions and we were by now in about 34th place, three places and three points off the bottom. All was not lost, however. Before and during dinner we had been working on the Picture Round. With the title of "Soulmates" this was surely right up our street. We had two sheets, each showing 24 pictures of people. We simply had to pair everybody on one sheet with somebody on the other sheet. Some were easy - Vivian Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara went with Clark Gable as Rhett Butler. Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas. Nigel Bruce as Watson clearly went with the silhouette of Sherlock Holmes. That drawing of an Egyptian queen must go with the classical bust of a young Roman. We thought that we had done quite well.

Then there was the Joker, which would double our score for the round in which we played it. We hadn't played ours yet, always hoping that the next round would prove easier than the one before. Now it was the last round, so we had to play it or waste it - not that we had a clue what "Critic's Choice" would entail. It turned out to be ten true/false questions. Had Matisse's Le Bateau hung upside down unnoticed for several weeks in a New York Gallery? Were Shakespeare, Mel Gibson, Oscar Wilde and one other who I have forgotten all the fathers of twins? Should Nottingham really be called Snottingham after its founder? We hummed, we ha-ed, we guessed. When the questionmaster, John Sergeant, read out the answers we had got nine right out of ten, and all but three of the Soulmates (well, who really can distinguish between the Wordsworths and the Brownings?)

When the final results were announced we had leapt up to about 12th place. The overall winners were Pan Macmillan, who squeezed out Orion in a tiebreak.

Not too bad for our first time at the event. We'll be back next year.

I had a cunning plan for the evening. We would do spectacularly well in the early rounds, thus raising our profile and ensuring that the hordes of publishers and agents present would flock to see us. This plan worked brilliantly all through the pre-dinner drinks (it's nice when an event gets sponsored by Dom Perignon) and was still on track as we sat down to our appetising appetisers, and then, as the first set of questions ("The Sports Pages") were read out, I realised that it wasn't going to be quite that easy. We did OK - we knew that Claudio had suggested that Benedict's beard had been used to stuff tennis balls, and that Rabbit Angstrom had played a game of basketball at the beginning of Rabbit Run (I never made it past chapter one, but luckily that was where this event took place), and we knew that Alice played croquet with a flamingo. We were less good at knowing what greasy ball had flown past James Joyce's face in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and couldn't remember who had played against the Dingley Dellers in the criket match in The Pickwick Papers. OK was never going to be enough in such company.

We did even worse in the second round ("Courtroom Sketch") and by the end of Round 3 ("Talk of the Town") it looked as if we were in severe danger of coming bottom out of the 37 tables taking part. So much for stunning the assembled cream of the literary scene with our intellect. Luckily the rest of the dinner was served at this point so we could concentrate on other things.

The fourth round ("Juke Box Jury") had yet more fiendish questions and we were by now in about 34th place, three places and three points off the bottom. All was not lost, however. Before and during dinner we had been working on the Picture Round. With the title of "Soulmates" this was surely right up our street. We had two sheets, each showing 24 pictures of people. We simply had to pair everybody on one sheet with somebody on the other sheet. Some were easy - Vivian Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara went with Clark Gable as Rhett Butler. Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas. Nigel Bruce as Watson clearly went with the silhouette of Sherlock Holmes. That drawing of an Egyptian queen must go with the classical bust of a young Roman. We thought that we had done quite well.

Then there was the Joker, which would double our score for the round in which we played it. We hadn't played ours yet, always hoping that the next round would prove easier than the one before. Now it was the last round, so we had to play it or waste it - not that we had a clue what "Critic's Choice" would entail. It turned out to be ten true/false questions. Had Matisse's Le Bateau hung upside down unnoticed for several weeks in a New York Gallery? Were Shakespeare, Mel Gibson, Oscar Wilde and one other who I have forgotten all the fathers of twins? Should Nottingham really be called Snottingham after its founder? We hummed, we ha-ed, we guessed. When the questionmaster, John Sergeant, read out the answers we had got nine right out of ten, and all but three of the Soulmates (well, who really can distinguish between the Wordsworths and the Brownings?)

When the final results were announced we had leapt up to about 12th place. The overall winners were Pan Macmillan, who squeezed out Orion in a tiebreak.

Not too bad for our first time at the event. We'll be back next year.

Sunday, 27 November 2005

Since these heyeroine pieces seem to be quite popular I have been back to the brilliant button maker and made a couple more brilliant buttons.

Perfect for linking to your favourite heyeroine in need of a slap?

I then went on to create the obvious partner for that one, which might come in handy if ever I get around to "Heyeros in need of a cuddle".

If you want to use them, go ahead - but do let me know all about it.

Perfect for linking to your favourite heyeroine in need of a slap?

I then went on to create the obvious partner for that one, which might come in handy if ever I get around to "Heyeros in need of a cuddle".

If you want to use them, go ahead - but do let me know all about it.

Heyeroines in need of a slap

13. Phoebe Marlow (Sylvester)

Quite how Phoebe Marlow managed to become a published author is something of a mystery, as she seems relentlessly to have broken most of the rules laid down for the advice and betterment of aspiring novelists.

Quite how Phoebe Marlow managed to become a published author is something of a mystery, as she seems relentlessly to have broken most of the rules laid down for the advice and betterment of aspiring novelists.

Her first questionable move was her choice of agent. Miss "Sibby" Battersby is not, to my knowledge, a member of any professional body for authors' agents, and has no prior experience of the editorial side of publishing. Indeed her only credential is that she has a cousin who is a junior partner in the publishing house of Newsham and Otley, although as they are, if not a vanity house, a house with more self-regard than any reputation for publishing romances, this hardly qualifies her to represent Miss Marlow. I can only assume that Phoebe had somehow discovered Miss Battersby's propensity to hit the gin pail and assumed that she must be Miss Snark.

Given Miss Battersby's lack of experience, qualifications and indeed any sign of innate ability, it is hardly surprising that her first and only move is to attempt to place The Lost Heir with Newsham and Otley. As publishers at the opposite end of the literary spectrum from the world of fictional romance, it is easy enough to see how they would react when presented with a hopelessly overwritten gothic extravaganza by an incompetent agent representing a naïve and trusting new writer. They would obviously snap it up on contract terms that would make the Society of Authors gibber before selling it on under considerably more advantageous terms to Anthony King Newman's operation. And what contract terms they are. The idea that the author should pay to have the book bound is still somewhat frowned upon by the Society of Authors, and many reputable agents would suggest that the author bearing all losses was coming it a little too brown. What Miss Battersby might have gained from this contract is unclear, much like the gin in which she would almost have certainly invested it.

Luckily Miss Marlow must by this stage have read a few how-to books, and while she does not go as far as sacking her agent she does manage to secure an advance (payable through her agent, who thus ensures that she can keep herself in mothers' ruin for a little while longer), although had she read beyond the blurbs on the back she might have noticed that her contract apparently gave her no royalties nor a two book deal, nor any clarity on translation or theatrical adaptation rights. This contract does, however seem to have forced Newsham and Otley into publishing The Lost Heir themselves, perhaps for fear that the vastly more experienced Mr Newman would hoodwink them the way they tried to hoodwink Miss Marlow.

As every writer knows, publication is just the beginning. To be successful a book must be marketed, and here Newsham and Otley's inexperience in the field of commercial fiction starts to show. They at least have the sense to ride the wave created by Glenarvon, but here their ideas seem to have run out.

Meanwhile Miss Marlow's reading of how-to books must have come on apace, as she seems to have spotted Newsham and Otley's faults, and contracted the Dowager Duchess of Salford to run her marketing. There is a long tradition of women of aristocratic background going into the marketing and PR business (although they are usually a little younger than Her Grace of Salford) and not without good reason: "Mama-Duchess" Rayne clearly knows her stuff. Despite it being some 60 years before Pasteur came up with the concept of viruses, the Dowager Duchess manages to launch an extremely successful viral marketing campaign, ensuring that The Lost Heir is talked about as the publishing sensation of the season. It is however when Lizzie Rayne ventures into the field of author PR that things become a bit shaky. Her plan is certainly bold; marrying her author off to a Duke would certainly get her talked about. Her plan is also a little self-serving, as the Duke in question is her own son, a relationship that is unlikely to go unremarked upon, even in the deeply nepotistic world of the haut ton. But where the Dowager Duchess really slips up is in not remembering that her client has been published anonymously, and as countless anonymous and pseudonymous writers have discovered, combining the mystique of a pen name with a sustained existence in the on dit columns is a tricky act to pull off. Where was Miss Marlow's agent at this point? Need we ask?

It is not surprising then that everything goes pear-shaped. On the one hand the anonymity strategy crashes and burns as Ianthe Rayne, that archetypal D-list celebrity, blows her cover resulting in nothing less than the cut direct from Lady Ribbleton. On the otherhand the connection with the Duke leads to Miss Marlow becoming entangled with the affairs of Sir Nugent Fotherby, of the Fotherby Tie and the silly Hessians - hardly the sort of company with whom an aspiring author would wish to become associated. Even the author tour to France seems to have been a hopeless fiasco, with nowhere expecting Miss Marlow to visit, no copies of The Lost Heir available, and the combination of Edmund and Chien once again proving that writing for children (and animals) is a less daunting prospect than working with them. Somehow Phoebe survives all this, and even ends up marrying her Duke (although with little sign of the PR spin from such an event contributing to her sales figures), but it seems to have been a somewhat fraught and conflict-ridden exercise throughout.

Surely it would have been so much more sensible for Miss Marlow to have simply written a killer synopsis and taken her chances in the Minerva Press slush pile?

Technorati Tags: heyeroines

13. Phoebe Marlow (Sylvester)

Quite how Phoebe Marlow managed to become a published author is something of a mystery, as she seems relentlessly to have broken most of the rules laid down for the advice and betterment of aspiring novelists.

Quite how Phoebe Marlow managed to become a published author is something of a mystery, as she seems relentlessly to have broken most of the rules laid down for the advice and betterment of aspiring novelists.Her first questionable move was her choice of agent. Miss "Sibby" Battersby is not, to my knowledge, a member of any professional body for authors' agents, and has no prior experience of the editorial side of publishing. Indeed her only credential is that she has a cousin who is a junior partner in the publishing house of Newsham and Otley, although as they are, if not a vanity house, a house with more self-regard than any reputation for publishing romances, this hardly qualifies her to represent Miss Marlow. I can only assume that Phoebe had somehow discovered Miss Battersby's propensity to hit the gin pail and assumed that she must be Miss Snark.

Given Miss Battersby's lack of experience, qualifications and indeed any sign of innate ability, it is hardly surprising that her first and only move is to attempt to place The Lost Heir with Newsham and Otley. As publishers at the opposite end of the literary spectrum from the world of fictional romance, it is easy enough to see how they would react when presented with a hopelessly overwritten gothic extravaganza by an incompetent agent representing a naïve and trusting new writer. They would obviously snap it up on contract terms that would make the Society of Authors gibber before selling it on under considerably more advantageous terms to Anthony King Newman's operation. And what contract terms they are. The idea that the author should pay to have the book bound is still somewhat frowned upon by the Society of Authors, and many reputable agents would suggest that the author bearing all losses was coming it a little too brown. What Miss Battersby might have gained from this contract is unclear, much like the gin in which she would almost have certainly invested it.

Luckily Miss Marlow must by this stage have read a few how-to books, and while she does not go as far as sacking her agent she does manage to secure an advance (payable through her agent, who thus ensures that she can keep herself in mothers' ruin for a little while longer), although had she read beyond the blurbs on the back she might have noticed that her contract apparently gave her no royalties nor a two book deal, nor any clarity on translation or theatrical adaptation rights. This contract does, however seem to have forced Newsham and Otley into publishing The Lost Heir themselves, perhaps for fear that the vastly more experienced Mr Newman would hoodwink them the way they tried to hoodwink Miss Marlow.

As every writer knows, publication is just the beginning. To be successful a book must be marketed, and here Newsham and Otley's inexperience in the field of commercial fiction starts to show. They at least have the sense to ride the wave created by Glenarvon, but here their ideas seem to have run out.

Meanwhile Miss Marlow's reading of how-to books must have come on apace, as she seems to have spotted Newsham and Otley's faults, and contracted the Dowager Duchess of Salford to run her marketing. There is a long tradition of women of aristocratic background going into the marketing and PR business (although they are usually a little younger than Her Grace of Salford) and not without good reason: "Mama-Duchess" Rayne clearly knows her stuff. Despite it being some 60 years before Pasteur came up with the concept of viruses, the Dowager Duchess manages to launch an extremely successful viral marketing campaign, ensuring that The Lost Heir is talked about as the publishing sensation of the season. It is however when Lizzie Rayne ventures into the field of author PR that things become a bit shaky. Her plan is certainly bold; marrying her author off to a Duke would certainly get her talked about. Her plan is also a little self-serving, as the Duke in question is her own son, a relationship that is unlikely to go unremarked upon, even in the deeply nepotistic world of the haut ton. But where the Dowager Duchess really slips up is in not remembering that her client has been published anonymously, and as countless anonymous and pseudonymous writers have discovered, combining the mystique of a pen name with a sustained existence in the on dit columns is a tricky act to pull off. Where was Miss Marlow's agent at this point? Need we ask?

It is not surprising then that everything goes pear-shaped. On the one hand the anonymity strategy crashes and burns as Ianthe Rayne, that archetypal D-list celebrity, blows her cover resulting in nothing less than the cut direct from Lady Ribbleton. On the otherhand the connection with the Duke leads to Miss Marlow becoming entangled with the affairs of Sir Nugent Fotherby, of the Fotherby Tie and the silly Hessians - hardly the sort of company with whom an aspiring author would wish to become associated. Even the author tour to France seems to have been a hopeless fiasco, with nowhere expecting Miss Marlow to visit, no copies of The Lost Heir available, and the combination of Edmund and Chien once again proving that writing for children (and animals) is a less daunting prospect than working with them. Somehow Phoebe survives all this, and even ends up marrying her Duke (although with little sign of the PR spin from such an event contributing to her sales figures), but it seems to have been a somewhat fraught and conflict-ridden exercise throughout.

Surely it would have been so much more sensible for Miss Marlow to have simply written a killer synopsis and taken her chances in the Minerva Press slush pile?

Technorati Tags: heyeroines

Tuesday, 22 November 2005

Heyeroines in need of a slap

12. Ancilla Trent (The Nonesuch)

Tempting as it is, I am not going to comment upon the fact that Miss Trent's parents appear to have blessed her with a name that makes her sound less like a romantic heroine, and more like a management consultancy partnership offering advisory services to the water and sewerage sector. Nor will I comment on the fact that she appears to live in a house named after one of the more humble classes of stationery consumables. After all, hard though it is to conceive, neither business consultants nor document binding solutions existed during the Regency, and Ancilla's parents must have had their reasons, much as her grandfather must have done when he named one of his sons after a chemical used in the dying process and still managed to spell it wrong. And if Ancilla can, as she makes quite clear, earn £150 a year as a Governess, her name cannot have been much of a hindrance.

Tempting as it is, I am not going to comment upon the fact that Miss Trent's parents appear to have blessed her with a name that makes her sound less like a romantic heroine, and more like a management consultancy partnership offering advisory services to the water and sewerage sector. Nor will I comment on the fact that she appears to live in a house named after one of the more humble classes of stationery consumables. After all, hard though it is to conceive, neither business consultants nor document binding solutions existed during the Regency, and Ancilla's parents must have had their reasons, much as her grandfather must have done when he named one of his sons after a chemical used in the dying process and still managed to spell it wrong. And if Ancilla can, as she makes quite clear, earn £150 a year as a Governess, her name cannot have been much of a hindrance.

Nor am I going to dwell much upon the bucolic delights of the village of Oversett, where our tale unfolds. It does not take much knowledge of the field of place name studies to conclude that a village bearing such a name must be a traditional home of badgers, but it rapidly becomes clear that this is no mere philological hangover. While the locals consisted merely of Shilbottles, Tumbys, Wrangles and Butterlaws one could imagine that this part of the country was no more than an outpost of Tolkien's Shire, but as soon as Mrs Underhill (an even more hobbity name than the rest), who, we should not forget, pays Ancilla £150 a year, contemplates sending a card to the Badgers we have an inkling that Yorkshire is not a lost corner of Middle Earth, but a hidden tendril of Narnia.

As this is a series of essays on heyeroines, it is not the place to dwell unduly upon our hero, except to note that in any civilised age a man with the outrageous name of Waldo Hawkridge, who combines a tendency to do a great deal for charidee with not liking to talk about it, could only be a disk jockey. Should we conclude from this that today's DJs are the spiritual descendents of the Corinthian set? Is there something about the precise control of the wheels of a phaeton that is transferable to the spinning of twin turntables? Would that other great Corinthian, Beau Wyndham, be happy doing the breakfast show or would he insist on the drive time slot? Alas, we shall never know.

But let us return to Miss Trent. I do not consider that she merits a slap simply for being tediously, relentlessly, unflappably nice. Nor can I condemn her for being the only woman in Oversett between the schoolroom and late matronhood (although I, and possibly the Bow Street Runners, would be interested to know what she did with all the other marriageable females of the village). Furthermore I will excuse her for having acquired a reputation for being able to manage the tantrums and hissy fits of the dreadful Miss Theophania Wield, despite showing no evidence that she has managed to achieve the slightest sustainable improvement in Tiffany's behaviour (and for which skill she pockets £150 a year).

No. Eminently censurable though these faults are, they pale into insignificance beside Miss Trent's greatest fault, which is this: she indulged in a Big Misunderstanding, and that is unforgiveable.

Here we have a woman whose analytical capabilities are such that from nothing but a crumpled riding habit, a hysterical maid and a missing bandbox she can determine that her charge has visited the vicarage, learned of an engagement that Ancilla herself did not know for sure had been entered into, returned home, and tricked a visitor to the area into carrying her to Leeds with the express intent of taking the stage to London to stay with an uncle. All entirely accurate. Yet at the same time we must suppose her so wet-goosish that, from an ambiguous passing remark by a man that she knows to be loose of tongue and far from steadfast in his views, she conjures up an inexplicably gothic image of a well-regarded and exceptionally mannered man of whom she has become fond as some devil-may-care rakehell capable of leaving a trail of by-blows across the country, and so devoid of sensibility that he can contemplate rounding them up and housing them in a country house in theNarnian Yorkshire countryside. And having conjured up this absurd fantasy Miss Trent, who claims to be able to quell Miss Wield with a glance, and disconcert her employer's neighbours with a few well chosen words (well worth £150 a year of anybody's money), is utterly unable to ask her beau just what he is actually up to.

I am afraid that it is all coming it a bit strong.

Technorati Tags: heyeroines

12. Ancilla Trent (The Nonesuch)

Tempting as it is, I am not going to comment upon the fact that Miss Trent's parents appear to have blessed her with a name that makes her sound less like a romantic heroine, and more like a management consultancy partnership offering advisory services to the water and sewerage sector. Nor will I comment on the fact that she appears to live in a house named after one of the more humble classes of stationery consumables. After all, hard though it is to conceive, neither business consultants nor document binding solutions existed during the Regency, and Ancilla's parents must have had their reasons, much as her grandfather must have done when he named one of his sons after a chemical used in the dying process and still managed to spell it wrong. And if Ancilla can, as she makes quite clear, earn £150 a year as a Governess, her name cannot have been much of a hindrance.

Tempting as it is, I am not going to comment upon the fact that Miss Trent's parents appear to have blessed her with a name that makes her sound less like a romantic heroine, and more like a management consultancy partnership offering advisory services to the water and sewerage sector. Nor will I comment on the fact that she appears to live in a house named after one of the more humble classes of stationery consumables. After all, hard though it is to conceive, neither business consultants nor document binding solutions existed during the Regency, and Ancilla's parents must have had their reasons, much as her grandfather must have done when he named one of his sons after a chemical used in the dying process and still managed to spell it wrong. And if Ancilla can, as she makes quite clear, earn £150 a year as a Governess, her name cannot have been much of a hindrance.Nor am I going to dwell much upon the bucolic delights of the village of Oversett, where our tale unfolds. It does not take much knowledge of the field of place name studies to conclude that a village bearing such a name must be a traditional home of badgers, but it rapidly becomes clear that this is no mere philological hangover. While the locals consisted merely of Shilbottles, Tumbys, Wrangles and Butterlaws one could imagine that this part of the country was no more than an outpost of Tolkien's Shire, but as soon as Mrs Underhill (an even more hobbity name than the rest), who, we should not forget, pays Ancilla £150 a year, contemplates sending a card to the Badgers we have an inkling that Yorkshire is not a lost corner of Middle Earth, but a hidden tendril of Narnia.

As this is a series of essays on heyeroines, it is not the place to dwell unduly upon our hero, except to note that in any civilised age a man with the outrageous name of Waldo Hawkridge, who combines a tendency to do a great deal for charidee with not liking to talk about it, could only be a disk jockey. Should we conclude from this that today's DJs are the spiritual descendents of the Corinthian set? Is there something about the precise control of the wheels of a phaeton that is transferable to the spinning of twin turntables? Would that other great Corinthian, Beau Wyndham, be happy doing the breakfast show or would he insist on the drive time slot? Alas, we shall never know.

But let us return to Miss Trent. I do not consider that she merits a slap simply for being tediously, relentlessly, unflappably nice. Nor can I condemn her for being the only woman in Oversett between the schoolroom and late matronhood (although I, and possibly the Bow Street Runners, would be interested to know what she did with all the other marriageable females of the village). Furthermore I will excuse her for having acquired a reputation for being able to manage the tantrums and hissy fits of the dreadful Miss Theophania Wield, despite showing no evidence that she has managed to achieve the slightest sustainable improvement in Tiffany's behaviour (and for which skill she pockets £150 a year).

No. Eminently censurable though these faults are, they pale into insignificance beside Miss Trent's greatest fault, which is this: she indulged in a Big Misunderstanding, and that is unforgiveable.

Here we have a woman whose analytical capabilities are such that from nothing but a crumpled riding habit, a hysterical maid and a missing bandbox she can determine that her charge has visited the vicarage, learned of an engagement that Ancilla herself did not know for sure had been entered into, returned home, and tricked a visitor to the area into carrying her to Leeds with the express intent of taking the stage to London to stay with an uncle. All entirely accurate. Yet at the same time we must suppose her so wet-goosish that, from an ambiguous passing remark by a man that she knows to be loose of tongue and far from steadfast in his views, she conjures up an inexplicably gothic image of a well-regarded and exceptionally mannered man of whom she has become fond as some devil-may-care rakehell capable of leaving a trail of by-blows across the country, and so devoid of sensibility that he can contemplate rounding them up and housing them in a country house in the

I am afraid that it is all coming it a bit strong.

Technorati Tags: heyeroines

Monday, 14 November 2005

A combination of redrafting Lord Alexander's Cipher; or, the Bridekirk Behemoth and some busy weekends seeing family and friends has left me neglectful of Wenlock. My apologies. I will try to get another heyeroine up during the course of the week.

Meanwhile if you are interested in historical fiction, particularly of a romantic disposition, then I can heartily recommend UK Historical Romance, a brand new blog set up by a group of writers of historical romance including Amanda Grange, Kate Allan, Melinda Hammond and Pamela Cleaver. It currently features the cover of Amanda Grange's latest, Darcy's Diary (which I took with me to the barber's on Saturday to indicate how I wanted my hair cut).

In addition to contributing to UK Historical Romance, Kate Allan has also started another blog, Marketing for Authors, which should be required readers for aspirant authors this side of the Atlantic at least (we do things slightly differently over here, so the leading blog on the subject, Buzz, Balls & Hype, needs a bit of translation).

Meanwhile if you are interested in historical fiction, particularly of a romantic disposition, then I can heartily recommend UK Historical Romance, a brand new blog set up by a group of writers of historical romance including Amanda Grange, Kate Allan, Melinda Hammond and Pamela Cleaver. It currently features the cover of Amanda Grange's latest, Darcy's Diary (which I took with me to the barber's on Saturday to indicate how I wanted my hair cut).

In addition to contributing to UK Historical Romance, Kate Allan has also started another blog, Marketing for Authors, which should be required readers for aspirant authors this side of the Atlantic at least (we do things slightly differently over here, so the leading blog on the subject, Buzz, Balls & Hype, needs a bit of translation).

Tuesday, 8 November 2005

Beau Brummell, The Ultimate Dandy by Ian Kelly

More than any other single person, with the possible exception of the Prince himself, George Bryan Brummell epitomised the "Regency Age" (which I tend to define as lasting from about 1780 to 1830). He was described by Byron as one of the "three great men of our age" alongside Napoleon and Byron himself. "But of we three," the poet continued, "the greatest of all is Brummell." In his essay on Dandyism, Who is a Dandy, George Walden suggests that the modern world is defined by three things: science & technology; liberal economics; and fashion. He suggests therefore that the three most important influences on today's society are Charles Darwin, Adam Smith, and George Bryan Brummell. Does Brummell's life match up to such glowing encomia, and does Ian Kelly's biography match up to its subject? While the answer to that first question is open to debate, the answer to the second is undoubtedly yes.

Ian Kelly does more than just recount Brummell's life story. He places it within its context, in terms of social, economic and political history. He begins with London in the mid-18th Century, where Beau Brummell's grandfather William was employed as servant to an MP from Hertfordshire, and where his grandmother, the daughter of a pastrycook, was a washerwoman. From this humble beginning William did well, through hard work and loyal service, and his employer was sufficiently impressed that he helped William's son Billy secure an appointment as office boy to another MP, Charles Jenkinson, later Lord Liverpool. Billy's own diligence secured him rapid preferment and he became an underclerk at the Treasury, working for Charles Townshend, and then his successor as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord North. When North became Prime Minister, Billy Brummell followed him to Downing Street, and, as was the way of such things, in the course of his duties there he amassed a fortune, and an apartment at Hampton Court where, having married his courtesan mistress on the King's orders, he raised a family of two boys, William and George Bryan, and one daughter, Maria.

In 1786, at the age of eight, Brummell went up to Eton alongside his older brother, where he studied for six years. Kelly shows that this was an important episode in Brummell's life. It was, he argues, in his role as a Poleman in Eton's raucous Ad Montem festivities that Brummell found the spare minimalist style of dress that he perfected during his adult life, and which is still at the heart of men's fashion today. It was at Eton that Brummell's first encounter with the opposite sex is recorded, in the form of a noisy serenading of the headmaster's daughter from below her window.

After Eton came Oxford, but not before another important amatory episode, Brummell's brief and unhappy relationship with the daughter of his parents' neighbours at Hampton Court, Julia Storer, who later achieved notoriety alongside Harriette Wilson and her sister Amy as the "Three Graces" of the demi-monde.

After Oxford Brummell joined the army. He did not join just any regiment, but, thanks to his father's fortune and contacts in the fashionable and political world or perhaps his own encounters with the heir to the throne, he was able to join the 10th regiment of Light Dragoons, whose Colonel-in-Chief was the Prince of Wales, and so which was destined not to serve abroad. The Prince of Wales' Own were modelled in drill and uniform on European Hussar regiments, among whose virtues are spectacular (and very expensive) uniforms. It was, Kelly suggests, his time in the army that honed the rhetorical whimsey at which Brummell had shown himself adept at Eton and Oxford into the darker wit that he deployed so readily in later years. Brummell sold out late in 1798.

All this serves as the scene-setter for the period in his life for which Brummell is best known, the years from 1799 to 1816 where he ruled London Society as the arbiter of elegance. For a biographer this period poses something of a problem, in that very little actually happened. Kelly negotiates this brilliantly by describing Brummell's life in terms of "a day in the high life", taking us through the morning: Brummell's famous levée, and the circle of friends that attended it; his choice of tailors and other suppliers, the afternoon: riding on Rotten Row; visiting Brooke's, White's and Watier's, the evening: visiting the theatre; attending that famous Seventh Heaven of the Fashionable World, and then on into the demi-monde, where the seeds of his downfall were eventually sown.

This central section of Kelly's book contains the best account of the life of the haut ton in early 19th Century London that I have come across. It is certainly more reliable than Venetia Murray's High Society in the Regency Period, and the copious bibliography is a great blessing too. Kelly has been both thorough and meticulous in his research.

From 1816 Brummell's life begins its gradual decline as his debts and syphilis take their toll. Once Brummell moves to France, never to return (Kelly considers, but tends not to favour, the suggestion that an entry in Berry Brothers' weighing book from 1821 is a genuine indication of Brummell's visiting London that year), the focus of the book moves away from the glittering world that he left behind and concentrates on his activities in Calais and then, from 1830, Caen. One of Kelly's great finds in researching this book was the detail of Brummell's last days as venereal disease destroyed his body and his mind. The last few chapters of the book are quite harrowing reading, as Kelly does not flinch from a comprehensive account of the pathology of tertiary syphilis, alongside his description of Brummell's increasing penury and his desperate attempts to seek support from his old friends. Brummell died on 30 March, 1840 in the Bon Sauveur asylum in Caen.

Kelly opens Beau Brummell with a short essay on what Dandyism has meant, in Brummell's time and our own. He ends with an epilogue on Brummell's legacy, tracing his influence through later dandies such as Oscar Wilde and Nöel Coward to the likes of Jarvis Cocker, his overwhelming influence on men's tailoring and even, thanks to Coco Chanel, women's fashion. While Brummell has most influenced the English, the French and the Americans, he can also be seen as part of the inspiration for Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, and even Nabokov's Humbert Humbert in Lolita.

Beau Brummell is illustrated with both colour prints and black-and-white drawings, including a useful map of fashionable London in 1800. Kelly's written style is very easy to read (although the book's physical bulk makes it rather unsuitable for reading on the bus or tube).

As a reference book for the Regency Age, as well as a comprehensive account of a remarkable individual, I unhesitatingly recommend this book to you all.

Beau Brummell, The Ultimate Dandy by Ian Kelly, Hodder and Stoughton, 2005. £20-00

Technorati Tags: book+review

More than any other single person, with the possible exception of the Prince himself, George Bryan Brummell epitomised the "Regency Age" (which I tend to define as lasting from about 1780 to 1830). He was described by Byron as one of the "three great men of our age" alongside Napoleon and Byron himself. "But of we three," the poet continued, "the greatest of all is Brummell." In his essay on Dandyism, Who is a Dandy, George Walden suggests that the modern world is defined by three things: science & technology; liberal economics; and fashion. He suggests therefore that the three most important influences on today's society are Charles Darwin, Adam Smith, and George Bryan Brummell. Does Brummell's life match up to such glowing encomia, and does Ian Kelly's biography match up to its subject? While the answer to that first question is open to debate, the answer to the second is undoubtedly yes.

Ian Kelly does more than just recount Brummell's life story. He places it within its context, in terms of social, economic and political history. He begins with London in the mid-18th Century, where Beau Brummell's grandfather William was employed as servant to an MP from Hertfordshire, and where his grandmother, the daughter of a pastrycook, was a washerwoman. From this humble beginning William did well, through hard work and loyal service, and his employer was sufficiently impressed that he helped William's son Billy secure an appointment as office boy to another MP, Charles Jenkinson, later Lord Liverpool. Billy's own diligence secured him rapid preferment and he became an underclerk at the Treasury, working for Charles Townshend, and then his successor as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord North. When North became Prime Minister, Billy Brummell followed him to Downing Street, and, as was the way of such things, in the course of his duties there he amassed a fortune, and an apartment at Hampton Court where, having married his courtesan mistress on the King's orders, he raised a family of two boys, William and George Bryan, and one daughter, Maria.

In 1786, at the age of eight, Brummell went up to Eton alongside his older brother, where he studied for six years. Kelly shows that this was an important episode in Brummell's life. It was, he argues, in his role as a Poleman in Eton's raucous Ad Montem festivities that Brummell found the spare minimalist style of dress that he perfected during his adult life, and which is still at the heart of men's fashion today. It was at Eton that Brummell's first encounter with the opposite sex is recorded, in the form of a noisy serenading of the headmaster's daughter from below her window.

After Eton came Oxford, but not before another important amatory episode, Brummell's brief and unhappy relationship with the daughter of his parents' neighbours at Hampton Court, Julia Storer, who later achieved notoriety alongside Harriette Wilson and her sister Amy as the "Three Graces" of the demi-monde.

After Oxford Brummell joined the army. He did not join just any regiment, but, thanks to his father's fortune and contacts in the fashionable and political world or perhaps his own encounters with the heir to the throne, he was able to join the 10th regiment of Light Dragoons, whose Colonel-in-Chief was the Prince of Wales, and so which was destined not to serve abroad. The Prince of Wales' Own were modelled in drill and uniform on European Hussar regiments, among whose virtues are spectacular (and very expensive) uniforms. It was, Kelly suggests, his time in the army that honed the rhetorical whimsey at which Brummell had shown himself adept at Eton and Oxford into the darker wit that he deployed so readily in later years. Brummell sold out late in 1798.

All this serves as the scene-setter for the period in his life for which Brummell is best known, the years from 1799 to 1816 where he ruled London Society as the arbiter of elegance. For a biographer this period poses something of a problem, in that very little actually happened. Kelly negotiates this brilliantly by describing Brummell's life in terms of "a day in the high life", taking us through the morning: Brummell's famous levée, and the circle of friends that attended it; his choice of tailors and other suppliers, the afternoon: riding on Rotten Row; visiting Brooke's, White's and Watier's, the evening: visiting the theatre; attending that famous Seventh Heaven of the Fashionable World, and then on into the demi-monde, where the seeds of his downfall were eventually sown.

This central section of Kelly's book contains the best account of the life of the haut ton in early 19th Century London that I have come across. It is certainly more reliable than Venetia Murray's High Society in the Regency Period, and the copious bibliography is a great blessing too. Kelly has been both thorough and meticulous in his research.

From 1816 Brummell's life begins its gradual decline as his debts and syphilis take their toll. Once Brummell moves to France, never to return (Kelly considers, but tends not to favour, the suggestion that an entry in Berry Brothers' weighing book from 1821 is a genuine indication of Brummell's visiting London that year), the focus of the book moves away from the glittering world that he left behind and concentrates on his activities in Calais and then, from 1830, Caen. One of Kelly's great finds in researching this book was the detail of Brummell's last days as venereal disease destroyed his body and his mind. The last few chapters of the book are quite harrowing reading, as Kelly does not flinch from a comprehensive account of the pathology of tertiary syphilis, alongside his description of Brummell's increasing penury and his desperate attempts to seek support from his old friends. Brummell died on 30 March, 1840 in the Bon Sauveur asylum in Caen.

Kelly opens Beau Brummell with a short essay on what Dandyism has meant, in Brummell's time and our own. He ends with an epilogue on Brummell's legacy, tracing his influence through later dandies such as Oscar Wilde and Nöel Coward to the likes of Jarvis Cocker, his overwhelming influence on men's tailoring and even, thanks to Coco Chanel, women's fashion. While Brummell has most influenced the English, the French and the Americans, he can also be seen as part of the inspiration for Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, and even Nabokov's Humbert Humbert in Lolita.

Beau Brummell is illustrated with both colour prints and black-and-white drawings, including a useful map of fashionable London in 1800. Kelly's written style is very easy to read (although the book's physical bulk makes it rather unsuitable for reading on the bus or tube).

As a reference book for the Regency Age, as well as a comprehensive account of a remarkable individual, I unhesitatingly recommend this book to you all.

Beau Brummell, The Ultimate Dandy by Ian Kelly, Hodder and Stoughton, 2005. £20-00

Technorati Tags: book+review

Sunday, 6 November 2005

I created this little blog button at the Brilliant Button Maker site. Now all I need to do is come up with some sort of practical use for it.

I created this little blog button at the Brilliant Button Maker site. Now all I need to do is come up with some sort of practical use for it.Here's another one which is perhaps that little bit more specialist. Thanks to Niles for alerting me to this useful facility.

Heyeroines in need of a slap

11. Deborah Grantham (Faro's Daughter)

Any establishment that spends £70 on green peas for every £42 that it spends on champagne (chapter 4 - Wenlock does the maths so you don't have to) has obviously got something seriously wrong with it. In crossing that threshold in St James's Square Max Ravenscar is stumbling into something more than your common or garden gambling hell. That he initially gets the wrong end of the stick is shown by his second visit, when he comes supplied with some spare whiplashes. Clearly he reckons that there are some things that Priddy's Foreign Warehouse and Vaults cannot supply, and I don't just mean Best K.Q. iron, faggoted edgeways.

It is probably on this second visit that he discovers what is wrong. Lady Bellingham's establishment is not just suffering from bizarre gastronomy and the pursuit of exotic ironware. The colour scheme is highly questionable with the yellow saloon hosting first Miss Grantham in a green dress (presumably intended to go with the peas) and then Sir James Filey in puce (Ravenscar, we learn in chapter 17, is much more conservative in his tastes, spending much of his time in a brown study). However the reason for such disastrous combinations quickly becomes apparent. Miss Grantham suffers from Daltonism: perhaps deuteranomalous tricomacy, tritanopic dichromacy or even achromatopsia (colour blindness - Wenlock does the long words so you can be impressed). This becomes quite obvious when she starts sewing coquelicot ribbons onto a green and white striped dress and wishes to accessorise this outfit with garnets.

Suddenly the reasons for the significant losses suffered by Lady Bellingham become explicable. Refusing to admit to her problem, Miss Grantham has been attempting to play cards, and run EO tables while unable to see what she is actually doing. Without colour cues to allow her to sum up gaming situations at a glance she is always going to be at a disadvantage, and it is her poor aunt who has to bear the cost of the inevitable losses.

Luckily for Miss Grantham, Ravenscar has a solution. Just as Mad Margaret from Ruddigore could be calmed by Sir Despard Murgatroyd's occasional use of the word "Basingstoke", so Miss Grantham can be alerted when she is handling something scarlet or green by Ravenscar's whispering "Jezebel" or "Jade" accordingly.

He never does explain what colour he means by "Doxy".

Technorati Tags: heyeroines

11. Deborah Grantham (Faro's Daughter)

Any establishment that spends £70 on green peas for every £42 that it spends on champagne (chapter 4 - Wenlock does the maths so you don't have to) has obviously got something seriously wrong with it. In crossing that threshold in St James's Square Max Ravenscar is stumbling into something more than your common or garden gambling hell. That he initially gets the wrong end of the stick is shown by his second visit, when he comes supplied with some spare whiplashes. Clearly he reckons that there are some things that Priddy's Foreign Warehouse and Vaults cannot supply, and I don't just mean Best K.Q. iron, faggoted edgeways.

It is probably on this second visit that he discovers what is wrong. Lady Bellingham's establishment is not just suffering from bizarre gastronomy and the pursuit of exotic ironware. The colour scheme is highly questionable with the yellow saloon hosting first Miss Grantham in a green dress (presumably intended to go with the peas) and then Sir James Filey in puce (Ravenscar, we learn in chapter 17, is much more conservative in his tastes, spending much of his time in a brown study). However the reason for such disastrous combinations quickly becomes apparent. Miss Grantham suffers from Daltonism: perhaps deuteranomalous tricomacy, tritanopic dichromacy or even achromatopsia (colour blindness - Wenlock does the long words so you can be impressed). This becomes quite obvious when she starts sewing coquelicot ribbons onto a green and white striped dress and wishes to accessorise this outfit with garnets.

Suddenly the reasons for the significant losses suffered by Lady Bellingham become explicable. Refusing to admit to her problem, Miss Grantham has been attempting to play cards, and run EO tables while unable to see what she is actually doing. Without colour cues to allow her to sum up gaming situations at a glance she is always going to be at a disadvantage, and it is her poor aunt who has to bear the cost of the inevitable losses.

Luckily for Miss Grantham, Ravenscar has a solution. Just as Mad Margaret from Ruddigore could be calmed by Sir Despard Murgatroyd's occasional use of the word "Basingstoke", so Miss Grantham can be alerted when she is handling something scarlet or green by Ravenscar's whispering "Jezebel" or "Jade" accordingly.

He never does explain what colour he means by "Doxy".

Technorati Tags: heyeroines

Friday, 4 November 2005

Anybody who has ever wondered how authors collaborate to produce a single work should pop over to A Regency Invitation, where the three authors of A Regency Invitation - Nicola Cornick, Joanna Maitland and Elizabeth Rolls - are blogging the hundreds of e-mails that they exchanged in the course of writing their three interlocking stories set against the background of a Regency Country House party.

Wednesday, 2 November 2005

Alex has tagged me (serves me right for doing the same to her a few weeks back). She wants me to answer a few questions.

Three screen names that you've had: Wenlock; Beau Bowden; Constantine Maroulis (sorry).

Three things you like about yourself: my sense of humour; my writing style; my eyes.

Three things you don't like about yourself: the fact that I snore; my tendency to procrastinate; I'll add the third one tomorrow.

Three parts of your heritage: generation after generation of Derbyshire textile workers on my father's father's side; Lincolnshire clergymen on my mother's father's side; and Russian Jewish emigrés on my mother's mother's side.

Three things that scare you: ignorance; madness; the thought of dying.

Three of your everyday essentials: theguardian; strong black coffee; fresh air.

Three things you are wearing right now: a rugby shirt; my new Paul Smith half boots; a thoughtful expression.

Three of your favorite songs: Boulder to Birmingham (Emmylou Harris); Save it for a Rainy Day (The Jayhawks); Thunder Road (Bruce Springsteen)

Three things you want in a relationship: wide horizons; laughter; not having to try hard all of the time.

Two truths and a lie: George is Will's son; George is Ed's son; it will all end in tears.

Three things you can't live without: my family; my radio; my writing.

Three places you want to go on vacation: Finland in the Winter; Venice in the Spring; Uzbekistan in the days of Tamburlaine.

Three things you just can't do: bowl a leg break; speak Chinese; sing in tune.

Three kids names: Giles, Isobel, Fay

Three things you want to do before you die: walk in the high Pamirs; gallop full-tilt across the English countryside; dine on honeydew and drink the milk of paradise.

Three celeb crushes: Louise Brooks; Joan Baez; Charlotte Green.

Three of your favorite musicians: Richard Thompson; Tom Waits; John Tams.

Three physical things about the opposite sex that appeal to you: expressive eyes; a slim figure; a clear complexion.

Three of your favorite hobbies: cross-country skiing; cooking; solving cryptic crosswords

Three things you really want to do badly right now: finish my redrafting; find an agent; get a contract.

Three careers you're considering/you've considered: novelist; academic; spy.

Three ways that you are stereotypically a boy: I ride a motorbike; I like prog rock; I drink real ale.

Three ways that you are stereotypically a girl: I write romantic fiction; I care about footwear; I think that I am too fat.

Three people that I would like to see post this meme: Kate; Candy; Gabriele.

Three screen names that you've had: Wenlock; Beau Bowden; Constantine Maroulis (sorry).

Three things you like about yourself: my sense of humour; my writing style; my eyes.

Three things you don't like about yourself: the fact that I snore; my tendency to procrastinate; I'll add the third one tomorrow.

Three parts of your heritage: generation after generation of Derbyshire textile workers on my father's father's side; Lincolnshire clergymen on my mother's father's side; and Russian Jewish emigrés on my mother's mother's side.

Three things that scare you: ignorance; madness; the thought of dying.

Three of your everyday essentials: theguardian; strong black coffee; fresh air.

Three things you are wearing right now: a rugby shirt; my new Paul Smith half boots; a thoughtful expression.

Three of your favorite songs: Boulder to Birmingham (Emmylou Harris); Save it for a Rainy Day (The Jayhawks); Thunder Road (Bruce Springsteen)

Three things you want in a relationship: wide horizons; laughter; not having to try hard all of the time.

Two truths and a lie: George is Will's son; George is Ed's son; it will all end in tears.

Three things you can't live without: my family; my radio; my writing.

Three places you want to go on vacation: Finland in the Winter; Venice in the Spring; Uzbekistan in the days of Tamburlaine.

Three things you just can't do: bowl a leg break; speak Chinese; sing in tune.

Three kids names: Giles, Isobel, Fay

Three things you want to do before you die: walk in the high Pamirs; gallop full-tilt across the English countryside; dine on honeydew and drink the milk of paradise.

Three celeb crushes: Louise Brooks; Joan Baez; Charlotte Green.

Three of your favorite musicians: Richard Thompson; Tom Waits; John Tams.

Three physical things about the opposite sex that appeal to you: expressive eyes; a slim figure; a clear complexion.

Three of your favorite hobbies: cross-country skiing; cooking; solving cryptic crosswords

Three things you really want to do badly right now: finish my redrafting; find an agent; get a contract.

Three careers you're considering/you've considered: novelist; academic; spy.

Three ways that you are stereotypically a boy: I ride a motorbike; I like prog rock; I drink real ale.

Three ways that you are stereotypically a girl: I write romantic fiction; I care about footwear; I think that I am too fat.

Three people that I would like to see post this meme: Kate; Candy; Gabriele.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)