Regular readers will have noticed that I have not posted since early October. This hiatus was initially caused by the moving of Wenlock Towers some half a mile to the South, and its rebuilding in a the modern Palladian style, facing in a new direction. Such works take time.

However that disruption has been followed by various other changes to my circumstances (mainly a new role at my place of gainful employ), which are leaving me less time both to read and to write articles for this blog.

At the same time my agent and I have reluctantly concluded that Lord Alexander's Cipher; or, the Bridekirk Behemoth is unlikely to find a publisher (although the latest highly complimentary rejection described it as "Buchanesque", which is nice) so I must turn my attentions to producing something new.

All of which is building up to my saying that Wenlock will be going into indefinite hibernation. I hope to return to the Blogosphere in due course, either here or in a new form, but until then I would like to thank all my readers and commenters for the support that you have provided me over the last year and several months.

Wednesday, 15 November 2006

Sunday, 8 October 2006

It's Cheltenham Literary Festival time, and while I am not going to many events, I did go to a very interesting session yesterday called New Grub Street, and featuring Scott Pack, former chief buyer for Waterstones, now part of The Friday Project, Susan Hill, a writer who set up a publishing house, Ion Trewin, the chair of the Festival Committee and former Literary Editor of the Times, publisher and many other things, Patrick Neate, writer and guest director for the first weekend of the Festival, and Danuta Kean, booktrade commentator and former chair of the Romantic Novel of the Year judges. They said a great deal of interest, but today I want to focus on one thing, a cautionary tale mentioned in passing by Susan Hill.

I don't know whether you remember, but a couple of years ago Hill, having set up Long Barn Books as a small publisher, held a competition to select the first work of fiction that she would publish. The competition attracted 3,741 entrants and the winner was Helen Slavin's The Extra Large Medium.

I don't know whether you remember, but a couple of years ago Hill, having set up Long Barn Books as a small publisher, held a competition to select the first work of fiction that she would publish. The competition attracted 3,741 entrants and the winner was Helen Slavin's The Extra Large Medium.

According to the Long Barn website:

I don't know whether you remember, but a couple of years ago Hill, having set up Long Barn Books as a small publisher, held a competition to select the first work of fiction that she would publish. The competition attracted 3,741 entrants and the winner was Helen Slavin's The Extra Large Medium.

I don't know whether you remember, but a couple of years ago Hill, having set up Long Barn Books as a small publisher, held a competition to select the first work of fiction that she would publish. The competition attracted 3,741 entrants and the winner was Helen Slavin's The Extra Large Medium.According to the Long Barn website:

A US publishing deal has been agreed.The book was published in May. Long Barn gave it a 2,000 print run, and secured a 3 for 2 deal with Waterstones, who took 1,600 copies. It was in the shops when the reviews came out - good reviews mainly, and more than usual because of the background. And Beryl Bainbridge had a shout on the cover:

An Australian/New Zealand publishing deal has been agreed.

And, advance orders are so good the novel is REPRINTING BEFORE PUBLICATION. !!

"The Extra Large Medium is very, very good... no unnecessary words or explanations, just good, and also witty. A highly original talent. Helen Slavin should be encouraged, I've no doubt about that."At yesterday's talk, Susan Hill said that the returns window had just about closed, and Waterstones had returned 1,400 copies.

Wednesday, 4 October 2006

The last part of Reader, I Married Him was broadcast on Monday evening, and focused on heroines.

After my disappointment with the selection of heroes in episode 2 I am delighted to report that Daisy Goodwin and co did a very much better job with heroines, looking at them from the 18th Century Gothic novels through to Bridget Jones.

Goodwin dismissed the heroines of Gothic novels (such as The Castle of Otranto, from which she quoted) as rather feeble. While I have a certain soft spot for the more, well, gothic of the Gothic novels (Matthew Lewis's (left) The Monk, for instance), I cannot dispute any suggestion that the heroines are not their strongest point.

Goodwin dismissed the heroines of Gothic novels (such as The Castle of Otranto, from which she quoted) as rather feeble. While I have a certain soft spot for the more, well, gothic of the Gothic novels (Matthew Lewis's (left) The Monk, for instance), I cannot dispute any suggestion that the heroines are not their strongest point.

Jane Austen must have had the same views, as she satirised gothic in Northanger Abbey, and came up with much stronger heroines in her later books. Goodwin, predictably, picked out Elizabeth Bennet for particular scrutiny, illustrated by Jennifer Ehle. Personally I think that Emma Woodhouse might have been an even better case study, but the best recent adaptation was not made by the BBC.

Jane Austen must have had the same views, as she satirised gothic in Northanger Abbey, and came up with much stronger heroines in her later books. Goodwin, predictably, picked out Elizabeth Bennet for particular scrutiny, illustrated by Jennifer Ehle. Personally I think that Emma Woodhouse might have been an even better case study, but the best recent adaptation was not made by the BBC.

From Austen we moved on to the Brontës, or rather Jane Eyre, with plenty of time to dwell on Toby Stephens and Ruth Wilson. Charlotte Brontë created Jane Eyre in part at least as a response to Austen's heroines and Goodwin brought out the contrast well, even if we did spend too long on the nature of governesses (but with nobody suggesting that they were "half of them detestable and the rest ridiculous, and all incubi").

From Austen we moved on to the Brontës, or rather Jane Eyre, with plenty of time to dwell on Toby Stephens and Ruth Wilson. Charlotte Brontë created Jane Eyre in part at least as a response to Austen's heroines and Goodwin brought out the contrast well, even if we did spend too long on the nature of governesses (but with nobody suggesting that they were "half of them detestable and the rest ridiculous, and all incubi").

Then it started to get interesting, for we moved into the 20th Century and alighted upon Madame Zalenska from Elinor Glyn's Three Weeks. Goodwin took the book to a reading group in Yorkshire, and concluded from their responses that time has not been kind to Elinor Glyn, and, judging by the clips from a 1977 production, neither were Thames Television, with Elizabeth Shepherd vamping for all she was worth over a rather bored looking tiger skin, and a young Simon McCorkindale as Paul Verdayne not really knowing where to look.

Then it started to get interesting, for we moved into the 20th Century and alighted upon Madame Zalenska from Elinor Glyn's Three Weeks. Goodwin took the book to a reading group in Yorkshire, and concluded from their responses that time has not been kind to Elinor Glyn, and, judging by the clips from a 1977 production, neither were Thames Television, with Elizabeth Shepherd vamping for all she was worth over a rather bored looking tiger skin, and a young Simon McCorkindale as Paul Verdayne not really knowing where to look.

It was no surprise that our next heroine saw Goodwin back in her crinoline and walking the streets of Atlanta in search of Scarlett O'Hara. I am probably alone in thinking that the world might be a better place if Margaret Mitchell had stuck to her original idea of naming her heroine "Pansy" and Melanie Hamilton "Permalia".

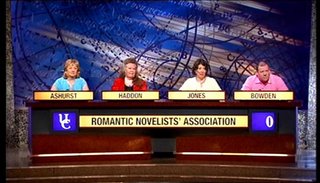

Unfortunately the urge to illustrate the whole discussion with old films and television dramatisations took a turn for the worse when Goodwin moved on to Georgette Heyer. Jenny Haddon, chair of the RNA, said some wonderful things about Heyer, as did Elizabeth Buchan and assorted others, but this was somewhat undercut by a short clip from the abominable film of The Reluctant Widow, and a brief extract from Venetia where she and Damerel discuss his orgies, accompanied by shots of neon signs from sex shops.

Unfortunately the urge to illustrate the whole discussion with old films and television dramatisations took a turn for the worse when Goodwin moved on to Georgette Heyer. Jenny Haddon, chair of the RNA, said some wonderful things about Heyer, as did Elizabeth Buchan and assorted others, but this was somewhat undercut by a short clip from the abominable film of The Reluctant Widow, and a brief extract from Venetia where she and Damerel discuss his orgies, accompanied by shots of neon signs from sex shops.

But at least Heyer was given plenty of space. The heroines of early feminist fiction (I am thinking of Isadora Wing, for instance) were skipped completely and we landed in the 1980s with Barbara Taylor Bradford's Emma Harte. The Yorkshire reading group found that she, too, had not aged well. Many had read it 25 years ago when it had seemed to capture some sort of Zeitgeist, but, like Kenneth More and Nyree Dawn Porter in The Forsyte Saga, it is one of those things that is best left to the fond embrace of memory. Bradford herself was good value in interview, however.

But at least Heyer was given plenty of space. The heroines of early feminist fiction (I am thinking of Isadora Wing, for instance) were skipped completely and we landed in the 1980s with Barbara Taylor Bradford's Emma Harte. The Yorkshire reading group found that she, too, had not aged well. Many had read it 25 years ago when it had seemed to capture some sort of Zeitgeist, but, like Kenneth More and Nyree Dawn Porter in The Forsyte Saga, it is one of those things that is best left to the fond embrace of memory. Bradford herself was good value in interview, however.

From Emma Harte's 1980s the final stop was Bridget Jones' 1990s, and the rise of Chick Lit.

From Emma Harte's 1980s the final stop was Bridget Jones' 1990s, and the rise of Chick Lit.

Along the way Goodwin asked some interesting questions about what a romantic heroine is looking for. In the 19th Century it was inevitably marriage - but not necessarily marriage on any terms. In the 21st Century it is a great deal more complicated than that. Goodwin's final session, with a group of schoolgirls, did not really come up with any suggestions about where the romantic heroine goes next, but it is something worth thinking about.

After my disappointment with the selection of heroes in episode 2 I am delighted to report that Daisy Goodwin and co did a very much better job with heroines, looking at them from the 18th Century Gothic novels through to Bridget Jones.

Goodwin dismissed the heroines of Gothic novels (such as The Castle of Otranto, from which she quoted) as rather feeble. While I have a certain soft spot for the more, well, gothic of the Gothic novels (Matthew Lewis's (left) The Monk, for instance), I cannot dispute any suggestion that the heroines are not their strongest point.

Goodwin dismissed the heroines of Gothic novels (such as The Castle of Otranto, from which she quoted) as rather feeble. While I have a certain soft spot for the more, well, gothic of the Gothic novels (Matthew Lewis's (left) The Monk, for instance), I cannot dispute any suggestion that the heroines are not their strongest point. Jane Austen must have had the same views, as she satirised gothic in Northanger Abbey, and came up with much stronger heroines in her later books. Goodwin, predictably, picked out Elizabeth Bennet for particular scrutiny, illustrated by Jennifer Ehle. Personally I think that Emma Woodhouse might have been an even better case study, but the best recent adaptation was not made by the BBC.

Jane Austen must have had the same views, as she satirised gothic in Northanger Abbey, and came up with much stronger heroines in her later books. Goodwin, predictably, picked out Elizabeth Bennet for particular scrutiny, illustrated by Jennifer Ehle. Personally I think that Emma Woodhouse might have been an even better case study, but the best recent adaptation was not made by the BBC. From Austen we moved on to the Brontës, or rather Jane Eyre, with plenty of time to dwell on Toby Stephens and Ruth Wilson. Charlotte Brontë created Jane Eyre in part at least as a response to Austen's heroines and Goodwin brought out the contrast well, even if we did spend too long on the nature of governesses (but with nobody suggesting that they were "half of them detestable and the rest ridiculous, and all incubi").

From Austen we moved on to the Brontës, or rather Jane Eyre, with plenty of time to dwell on Toby Stephens and Ruth Wilson. Charlotte Brontë created Jane Eyre in part at least as a response to Austen's heroines and Goodwin brought out the contrast well, even if we did spend too long on the nature of governesses (but with nobody suggesting that they were "half of them detestable and the rest ridiculous, and all incubi")."My dearest, don't mention governesses; the word makes me nervous. I have suffered a martyrdom from their incompetency and caprice. I thank Heaven I have now done with them!"

Then it started to get interesting, for we moved into the 20th Century and alighted upon Madame Zalenska from Elinor Glyn's Three Weeks. Goodwin took the book to a reading group in Yorkshire, and concluded from their responses that time has not been kind to Elinor Glyn, and, judging by the clips from a 1977 production, neither were Thames Television, with Elizabeth Shepherd vamping for all she was worth over a rather bored looking tiger skin, and a young Simon McCorkindale as Paul Verdayne not really knowing where to look.

Then it started to get interesting, for we moved into the 20th Century and alighted upon Madame Zalenska from Elinor Glyn's Three Weeks. Goodwin took the book to a reading group in Yorkshire, and concluded from their responses that time has not been kind to Elinor Glyn, and, judging by the clips from a 1977 production, neither were Thames Television, with Elizabeth Shepherd vamping for all she was worth over a rather bored looking tiger skin, and a young Simon McCorkindale as Paul Verdayne not really knowing where to look.It was no surprise that our next heroine saw Goodwin back in her crinoline and walking the streets of Atlanta in search of Scarlett O'Hara. I am probably alone in thinking that the world might be a better place if Margaret Mitchell had stuck to her original idea of naming her heroine "Pansy" and Melanie Hamilton "Permalia".

Unfortunately the urge to illustrate the whole discussion with old films and television dramatisations took a turn for the worse when Goodwin moved on to Georgette Heyer. Jenny Haddon, chair of the RNA, said some wonderful things about Heyer, as did Elizabeth Buchan and assorted others, but this was somewhat undercut by a short clip from the abominable film of The Reluctant Widow, and a brief extract from Venetia where she and Damerel discuss his orgies, accompanied by shots of neon signs from sex shops.

Unfortunately the urge to illustrate the whole discussion with old films and television dramatisations took a turn for the worse when Goodwin moved on to Georgette Heyer. Jenny Haddon, chair of the RNA, said some wonderful things about Heyer, as did Elizabeth Buchan and assorted others, but this was somewhat undercut by a short clip from the abominable film of The Reluctant Widow, and a brief extract from Venetia where she and Damerel discuss his orgies, accompanied by shots of neon signs from sex shops. But at least Heyer was given plenty of space. The heroines of early feminist fiction (I am thinking of Isadora Wing, for instance) were skipped completely and we landed in the 1980s with Barbara Taylor Bradford's Emma Harte. The Yorkshire reading group found that she, too, had not aged well. Many had read it 25 years ago when it had seemed to capture some sort of Zeitgeist, but, like Kenneth More and Nyree Dawn Porter in The Forsyte Saga, it is one of those things that is best left to the fond embrace of memory. Bradford herself was good value in interview, however.

But at least Heyer was given plenty of space. The heroines of early feminist fiction (I am thinking of Isadora Wing, for instance) were skipped completely and we landed in the 1980s with Barbara Taylor Bradford's Emma Harte. The Yorkshire reading group found that she, too, had not aged well. Many had read it 25 years ago when it had seemed to capture some sort of Zeitgeist, but, like Kenneth More and Nyree Dawn Porter in The Forsyte Saga, it is one of those things that is best left to the fond embrace of memory. Bradford herself was good value in interview, however. From Emma Harte's 1980s the final stop was Bridget Jones' 1990s, and the rise of Chick Lit.

From Emma Harte's 1980s the final stop was Bridget Jones' 1990s, and the rise of Chick Lit.Along the way Goodwin asked some interesting questions about what a romantic heroine is looking for. In the 19th Century it was inevitably marriage - but not necessarily marriage on any terms. In the 21st Century it is a great deal more complicated than that. Goodwin's final session, with a group of schoolgirls, did not really come up with any suggestions about where the romantic heroine goes next, but it is something worth thinking about.

Tuesday, 26 September 2006

It would be dreadfully churlish of me to be negative about the BBC devoting three hours of prime time (albeit digital-only) programming to a discussion of the Romantic Novel, but I feel that Reader, I Married Him could be doing so much more.

The second episode was broadcast last night (and will be repeated a few times later this week, including immediately after Jane Eyre next Sunday night). It focused on the Romantic Hero.

In fact for 55 of the 60 minutes it focused on just four heroes. The usual suspects: F Darcy, E Rochester, H Heathcliff* and R Butler.

While there was nothing wrong with what they said about any of them (except perhaps for poor Daisy Goodwin swanning around Atlanta in a Scarlett O'Hara dress, oh, and the cringe-making e-fit Mr Darcy bit) I couldn't see why the programme needed to spend so much time on just those four. Of course there was plenty of opportunity to show clips from the various film and television adaptations of Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, but this programme was supposed to be about romantic fiction: books, not films and television programmes. Goodwin even made the point that Austen gives virtually no physical description of Darcy, and part of his success must be the scope he gives readers to picture him however they like (the point of the e-fit segment). She then completely undermined her argument by tracking down Andrew Davies to talk about Colin Firth's wet shirt.

While there was nothing wrong with what they said about any of them (except perhaps for poor Daisy Goodwin swanning around Atlanta in a Scarlett O'Hara dress, oh, and the cringe-making e-fit Mr Darcy bit) I couldn't see why the programme needed to spend so much time on just those four. Of course there was plenty of opportunity to show clips from the various film and television adaptations of Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, but this programme was supposed to be about romantic fiction: books, not films and television programmes. Goodwin even made the point that Austen gives virtually no physical description of Darcy, and part of his success must be the scope he gives readers to picture him however they like (the point of the e-fit segment). She then completely undermined her argument by tracking down Andrew Davies to talk about Colin Firth's wet shirt.

I cannot deny that I found Goodwin's views on Heathcliff absolutely spot on, but did we need all those clips, and our Daisy strolling out on the wiley, windy moors? Did we need so many writers gushing over Darcy and Rochester? For having spent all of those 55 minutes on analysing these four old warhorses, there was no time left, for, for instance, a discussion about how the romantic hero has (or has not) evolved since the days of Jane Austen and the Brontës (I have to confess to having little time for Margaret Mitchell, whose book, had it not been made into such a sumptuous film, would probably be long-forgotten by now).

Given that she was talking to Jilly Cooper, Goodwin could have considered with her whether Rupert Campbell-Black was simply Darcy/Rochester/Heathcliff in modern dress, or something new. Talking to Maddie Rowe of Mills and Boon, Goodwin could have explored why, when Darcy/Rochester/Heathcliff are very English, Mills and Boon Modern heroes (the real Alpha males of the genre) are nowadays almost always foreign. Having talked to Sophie Kinsella and Marian Keyes for the first programme, they could have asked them how the chick-lit hero (or indeed the hero of romantic comedies of all sorts) gets away with not being an Alpha male, and what that says about readers' relationship with romantic comedy as opposed to straight romance - particularly given the "having an affair with the hero" concept that Katie Fforde talked about during the creative writing workshop that Goodwin attended.

Given that she was talking to Jilly Cooper, Goodwin could have considered with her whether Rupert Campbell-Black was simply Darcy/Rochester/Heathcliff in modern dress, or something new. Talking to Maddie Rowe of Mills and Boon, Goodwin could have explored why, when Darcy/Rochester/Heathcliff are very English, Mills and Boon Modern heroes (the real Alpha males of the genre) are nowadays almost always foreign. Having talked to Sophie Kinsella and Marian Keyes for the first programme, they could have asked them how the chick-lit hero (or indeed the hero of romantic comedies of all sorts) gets away with not being an Alpha male, and what that says about readers' relationship with romantic comedy as opposed to straight romance - particularly given the "having an affair with the hero" concept that Katie Fforde talked about during the creative writing workshop that Goodwin attended.

All in all I came away feeling that this was a bit of a missed opportunity to explore the romantic hero of today, rather than just wallowing in the same old same old.

* "It was the name of a son who died in childhood, and it has served him ever since, both for Christian and surname." Wuthering Heights, Chapter IV.

The second episode was broadcast last night (and will be repeated a few times later this week, including immediately after Jane Eyre next Sunday night). It focused on the Romantic Hero.

In fact for 55 of the 60 minutes it focused on just four heroes. The usual suspects: F Darcy, E Rochester, H Heathcliff* and R Butler.

While there was nothing wrong with what they said about any of them (except perhaps for poor Daisy Goodwin swanning around Atlanta in a Scarlett O'Hara dress, oh, and the cringe-making e-fit Mr Darcy bit) I couldn't see why the programme needed to spend so much time on just those four. Of course there was plenty of opportunity to show clips from the various film and television adaptations of Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, but this programme was supposed to be about romantic fiction: books, not films and television programmes. Goodwin even made the point that Austen gives virtually no physical description of Darcy, and part of his success must be the scope he gives readers to picture him however they like (the point of the e-fit segment). She then completely undermined her argument by tracking down Andrew Davies to talk about Colin Firth's wet shirt.

While there was nothing wrong with what they said about any of them (except perhaps for poor Daisy Goodwin swanning around Atlanta in a Scarlett O'Hara dress, oh, and the cringe-making e-fit Mr Darcy bit) I couldn't see why the programme needed to spend so much time on just those four. Of course there was plenty of opportunity to show clips from the various film and television adaptations of Pride and Prejudice, Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, but this programme was supposed to be about romantic fiction: books, not films and television programmes. Goodwin even made the point that Austen gives virtually no physical description of Darcy, and part of his success must be the scope he gives readers to picture him however they like (the point of the e-fit segment). She then completely undermined her argument by tracking down Andrew Davies to talk about Colin Firth's wet shirt.I cannot deny that I found Goodwin's views on Heathcliff absolutely spot on, but did we need all those clips, and our Daisy strolling out on the wiley, windy moors? Did we need so many writers gushing over Darcy and Rochester? For having spent all of those 55 minutes on analysing these four old warhorses, there was no time left, for, for instance, a discussion about how the romantic hero has (or has not) evolved since the days of Jane Austen and the Brontës (I have to confess to having little time for Margaret Mitchell, whose book, had it not been made into such a sumptuous film, would probably be long-forgotten by now).

Given that she was talking to Jilly Cooper, Goodwin could have considered with her whether Rupert Campbell-Black was simply Darcy/Rochester/Heathcliff in modern dress, or something new. Talking to Maddie Rowe of Mills and Boon, Goodwin could have explored why, when Darcy/Rochester/Heathcliff are very English, Mills and Boon Modern heroes (the real Alpha males of the genre) are nowadays almost always foreign. Having talked to Sophie Kinsella and Marian Keyes for the first programme, they could have asked them how the chick-lit hero (or indeed the hero of romantic comedies of all sorts) gets away with not being an Alpha male, and what that says about readers' relationship with romantic comedy as opposed to straight romance - particularly given the "having an affair with the hero" concept that Katie Fforde talked about during the creative writing workshop that Goodwin attended.

Given that she was talking to Jilly Cooper, Goodwin could have considered with her whether Rupert Campbell-Black was simply Darcy/Rochester/Heathcliff in modern dress, or something new. Talking to Maddie Rowe of Mills and Boon, Goodwin could have explored why, when Darcy/Rochester/Heathcliff are very English, Mills and Boon Modern heroes (the real Alpha males of the genre) are nowadays almost always foreign. Having talked to Sophie Kinsella and Marian Keyes for the first programme, they could have asked them how the chick-lit hero (or indeed the hero of romantic comedies of all sorts) gets away with not being an Alpha male, and what that says about readers' relationship with romantic comedy as opposed to straight romance - particularly given the "having an affair with the hero" concept that Katie Fforde talked about during the creative writing workshop that Goodwin attended.All in all I came away feeling that this was a bit of a missed opportunity to explore the romantic hero of today, rather than just wallowing in the same old same old.

* "It was the name of a son who died in childhood, and it has served him ever since, both for Christian and surname." Wuthering Heights, Chapter IV.

Tuesday, 19 September 2006

It's been a while since I mentioned Lord Alexander's Cipher; or, the Bridekirk Behemoth. For the last few of months it has been going out from Anne-Marie, my excellent agent, to a select number of editors, as is the way of these things, and, as is the way of these things, a few rejections have come back. Nothing like as many as J K Rowling received at this stage in her writing career, though, so I still have a way to go.

Today's update from Anne-Marie brought a very positive rejection:

So it looks like I will need to find a new title sooner rather than later - and certainly before Lord Alexander's Cipher; or, the Bridekirk Behemoth is submitted to Harper Collins.

Today's update from Anne-Marie brought a very positive rejection:

"very impressed with the fluency of the writing ... there's a huge amount of potential here for his career as a writer"but a rejection nonetheless. Anne-Marie also alerted me to news in the Bookseller that Harper Collins had just picked up a first novel about a search for treasure buried with Alexander the Great. Its title: The Alexander Cipher.

So it looks like I will need to find a new title sooner rather than later - and certainly before Lord Alexander's Cipher; or, the Bridekirk Behemoth is submitted to Harper Collins.

Sunday, 17 September 2006

Jojo Moyes (left) commented on my last post to say that Daisy Goodwin did have a valid point when she said:

Jojo Moyes (left) commented on my last post to say that Daisy Goodwin did have a valid point when she said:"female readers of romantic fiction were still generally dismissed by the men who run literary papers."And a similar point was made by Debbie Taylor (below), the editor of Mslexia, in a piece in today's Independent.

"Men simply don't like women's writers," Taylor says. "When men buy fiction they won't go near women's fiction." But with more women becoming publishing editors and newspaper literary editors, some of the hurdles women writers face are being removed. "It's not that they prefer books by women but situations that were actively hostile to women in the past aren't any more," she says.

The first quote there is something of a sweeping statement. Looking back at my holiday reading, I find that five of the six books that I read were by women. I would also challenge the way that Taylor switches between "women's fiction" and "books by women" as if these were the same thing.

The first quote there is something of a sweeping statement. Looking back at my holiday reading, I find that five of the six books that I read were by women. I would also challenge the way that Taylor switches between "women's fiction" and "books by women" as if these were the same thing.I have had a look at some recent broadsheet book review sections. Friday's Independent has five proper reviews of novels (I am ignoring short stories, poetry and children's fiction for the purposes of this exercise):

- Elizabeth Speller on The Fall of Troy by Peter Ackroyd

- Roz Kaveny on The Meaning of Night by Michael Cox

- Christina Patterson on Arlington Park by Rachel Cusk

- Wendy Brandmark on Special Topics in Calamity Physics by Marisha Pessl

- Shusha Guppy on Glass Houses by Sandra Howard

Saturday's theguardian has four full reviews of novels:

- Helen Dunmore on Restless by William Boyd

- James Lasdun on Arlington Park

- Peter Dempsey on Special Topics in Calamity Physics

- Rowan Pelling on Vocational Girl by "Rosa Mundi"

What does this tell us, if anything. One thing that struck me was that all the Independent reviews (with the exception of the Caryl Phillips mini) were written by women, but that is not immediately relevant.

Of the seven books given full reviews, four were by women and three by men. Of the paperback minis, four and a half were by men and one and a half by women (Maj Slowall is a woman and Per Wahloo a man). Of the crime minis one was by a man and three by women.

This is of course far too small a sample to draw firm conclusions upon, but it does not suggest an overwhelming bias towards male writers.

There is of course the fact that Crime is widely seen as popular fiction for men, and there is a crime round-up but no equivalent Romantic round-up, but that does not seem to have disadvantaged female writers per se.

But I said above that I did not accept that "books by women" and "women's fiction" are the same thing. Of the books reviewed, can any be considered "women's fiction"? I think that two of them can be. Sandra Howard's Glass Houses fits very comfortably into the category and so, arguably, does Vocational Girl (behind that Rosa Mundi pseudonym lurks Fay Weldon).

But I said above that I did not accept that "books by women" and "women's fiction" are the same thing. Of the books reviewed, can any be considered "women's fiction"? I think that two of them can be. Sandra Howard's Glass Houses fits very comfortably into the category and so, arguably, does Vocational Girl (behind that Rosa Mundi pseudonym lurks Fay Weldon). Glass Houses is given a very positive review ("Howard weaves the varied strands of her ingenious plot into a smooth and exciting narrative"), Vocational Girl less so ("fearful tosh"), but it appears that this week at least, two broadsheet newspapers have given over space to publish proper reviews not just of books by women, but of women's fiction.

Glass Houses is given a very positive review ("Howard weaves the varied strands of her ingenious plot into a smooth and exciting narrative"), Vocational Girl less so ("fearful tosh"), but it appears that this week at least, two broadsheet newspapers have given over space to publish proper reviews not just of books by women, but of women's fiction.Does two reviews out of nine reflect the relative sales of women's fiction when compared to fiction as a whole? Of course not.

But should the balance of books reviewed in broadsheet book sections reflect the overall pattern of sales? Now that is a question that I will return to at some later date.

Wednesday, 13 September 2006

Apologies for the gap in posting. It's the shock of going back to work after a long break.

In a diversion from what I did on my holidays, I thought that I would mention Reader, I Married Him, coming to BBC4 on Monday. If you watch you may even get a glimpse of Wenlock himself. I took part in a creative writing workshop with Katie Fforde that was filmed for the programme, and Daisy Goodwin interviewed me during a break in proceedings. I also answered a few vox pop questions at the RNA Awards dinner at the Savoy. Of course these may well have ended up on the cutting room floor.

In a diversion from what I did on my holidays, I thought that I would mention Reader, I Married Him, coming to BBC4 on Monday. If you watch you may even get a glimpse of Wenlock himself. I took part in a creative writing workshop with Katie Fforde that was filmed for the programme, and Daisy Goodwin interviewed me during a break in proceedings. I also answered a few vox pop questions at the RNA Awards dinner at the Savoy. Of course these may well have ended up on the cutting room floor.

Or maybe not. Perhaps my appearance will be used to support the apparent thesis of the programme, that men cannot write romance.

Whether or not I can write (good) romance is a matter of opinion, but the suggestion that "you can't have a really seriously-written romantic book written by a man" because male writers "lack insight into the ways of women" is patently absurd, and here's why.

If the only way to write credible female characters is to be a woman, then it must be because there is some aspect of being a woman that is fundamentally different from being a man. And this must be something that all women have in common with each other (within the fiction-reading world, at least), or else women couldn't write characters that were credible to all other women.

Now I know that there have been a few books published recently in the US that claim that male and female brains are indeed fundamentally different, particularly in terms of development through childhood and adolescence. Leonard Sax's Why Gender Matters: What Parents and Teachers Need to Know about the Emerging Science of Sex Differences is one of these, and Louann Brizendine's The Female Brain is another. Both books have been used to argue for single sex education, and they are both full of claims about fundamental differences between male and female brains, backed up with meaty looking citations of academic studies.

The trouble is that the studies do not actually support the claims in these books. They have been neatly debunked in places such as Language Log (here, here, and indeed here). There are no studies that do lend any support to there being significant differences between men and women in this respect. These books - and the Daisy Goodwin hypothesis - appear to rely on something akin to interpreting "men are taller than women" as meaning that all men are taller than any women.

ANd there's more. Goodwin is quoted as saying "female readers of romantic fiction were still generally dismissed by the men who run literary papers". Now, if men and women are so different that only women can write credible female characters, it is surely the case that only men can write credible male characters. Now most of the time this is not an issue, because female readers ("lacking insight into the minds of men" we must assume) would not spot the lack of credibility. But these mysterious "men who run literary papers" (what is a "literary paper"? Does theguardian count, or is it just the London Review of Books (edited by Mary-Kay Wilmers) and the TLS?) obviously do. Perhaps the whole image problem that romantic fiction has is due to the inability of female authors to write male characters?

Clearly this is rubbish. I would like to challenge Daisy Goodwin to read two or three romantic novels written by men and two or three written by women, without knowing who the authors are, and to declare which are which.

Not that this is really necessary, as women buy books by Jessica Stirling, Gill Sanderson, Jessica Blair, Emma Blair and many others without complaining that the authors - all men - "lack insight into the ways of women".

And if you do see me on the programme, remember that the camera adds pounds. And years. And the lighting can make almost anybody look as if they are losing their hair. You'd get a much better idea of what I look like over at Julie Cohen's site.

In a diversion from what I did on my holidays, I thought that I would mention Reader, I Married Him, coming to BBC4 on Monday. If you watch you may even get a glimpse of Wenlock himself. I took part in a creative writing workshop with Katie Fforde that was filmed for the programme, and Daisy Goodwin interviewed me during a break in proceedings. I also answered a few vox pop questions at the RNA Awards dinner at the Savoy. Of course these may well have ended up on the cutting room floor.

In a diversion from what I did on my holidays, I thought that I would mention Reader, I Married Him, coming to BBC4 on Monday. If you watch you may even get a glimpse of Wenlock himself. I took part in a creative writing workshop with Katie Fforde that was filmed for the programme, and Daisy Goodwin interviewed me during a break in proceedings. I also answered a few vox pop questions at the RNA Awards dinner at the Savoy. Of course these may well have ended up on the cutting room floor.Or maybe not. Perhaps my appearance will be used to support the apparent thesis of the programme, that men cannot write romance.

Whether or not I can write (good) romance is a matter of opinion, but the suggestion that "you can't have a really seriously-written romantic book written by a man" because male writers "lack insight into the ways of women" is patently absurd, and here's why.

If the only way to write credible female characters is to be a woman, then it must be because there is some aspect of being a woman that is fundamentally different from being a man. And this must be something that all women have in common with each other (within the fiction-reading world, at least), or else women couldn't write characters that were credible to all other women.

Now I know that there have been a few books published recently in the US that claim that male and female brains are indeed fundamentally different, particularly in terms of development through childhood and adolescence. Leonard Sax's Why Gender Matters: What Parents and Teachers Need to Know about the Emerging Science of Sex Differences is one of these, and Louann Brizendine's The Female Brain is another. Both books have been used to argue for single sex education, and they are both full of claims about fundamental differences between male and female brains, backed up with meaty looking citations of academic studies.

The trouble is that the studies do not actually support the claims in these books. They have been neatly debunked in places such as Language Log (here, here, and indeed here). There are no studies that do lend any support to there being significant differences between men and women in this respect. These books - and the Daisy Goodwin hypothesis - appear to rely on something akin to interpreting "men are taller than women" as meaning that all men are taller than any women.

ANd there's more. Goodwin is quoted as saying "female readers of romantic fiction were still generally dismissed by the men who run literary papers". Now, if men and women are so different that only women can write credible female characters, it is surely the case that only men can write credible male characters. Now most of the time this is not an issue, because female readers ("lacking insight into the minds of men" we must assume) would not spot the lack of credibility. But these mysterious "men who run literary papers" (what is a "literary paper"? Does theguardian count, or is it just the London Review of Books (edited by Mary-Kay Wilmers) and the TLS?) obviously do. Perhaps the whole image problem that romantic fiction has is due to the inability of female authors to write male characters?

Clearly this is rubbish. I would like to challenge Daisy Goodwin to read two or three romantic novels written by men and two or three written by women, without knowing who the authors are, and to declare which are which.

Not that this is really necessary, as women buy books by Jessica Stirling, Gill Sanderson, Jessica Blair, Emma Blair and many others without complaining that the authors - all men - "lack insight into the ways of women".

And if you do see me on the programme, remember that the camera adds pounds. And years. And the lighting can make almost anybody look as if they are losing their hair. You'd get a much better idea of what I look like over at Julie Cohen's site.

Monday, 28 August 2006

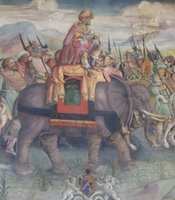

One cannot visit Italy without seeing some fantastic frescoes. Young Wenlock and I spent an hour or so queuing up outside the Vatican so that we could traipse through the museums before ending up in the Sistine Chapel, but given its reputation, the ceiling was always going to be a bit of a disappointment. I did quite like the Last Judgement, but Young Wenlock was more taken by Hannibal invading Italy on the wall of the Palazzo dei Conservatori.

One cannot visit Italy without seeing some fantastic frescoes. Young Wenlock and I spent an hour or so queuing up outside the Vatican so that we could traipse through the museums before ending up in the Sistine Chapel, but given its reputation, the ceiling was always going to be a bit of a disappointment. I did quite like the Last Judgement, but Young Wenlock was more taken by Hannibal invading Italy on the wall of the Palazzo dei Conservatori.Frescoes being found indoors, usually, and restrictions placed on taking photographs, the rest of this post will be illustrated by other people's pictures. What I have found, however, is that they rarely tend to capture the colourfulness of the real thing.

Siena has some wonderful frescoes. Simone Martini's Maesta of 1315, in the Palazzo Publico, is a great deal brighter and bluer than this picture (or the larger version that it links to) would have you believe. You might get a better idea of the colours from the Siena website, but their picture is so very blurred.

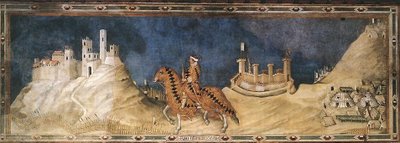

Siena has some wonderful frescoes. Simone Martini's Maesta of 1315, in the Palazzo Publico, is a great deal brighter and bluer than this picture (or the larger version that it links to) would have you believe. You might get a better idea of the colours from the Siena website, but their picture is so very blurred.Opposite the Maesta is a slightly controversial fresco, the Equestrian Portrait of Guidoriccio da Fogliano. If it really is also by Martini, as has long been believed, it would be one of the earliest Italian portraits. It would also have anachronistic castles. There is therefore an increasingly strong case (supported by suggestions of previous works underneath this one, that it is not by Martini, and that it may be a 16th Century fake. But even if it is a later work it is still spectacular.

Martini is good, but the really star of Sienese frescoes was Ambrogio Lorenzetti, whose Allegory of Good and Bad Government (1338-1340) is also in the Palazzo Publico. This is a set of six pictures. Two are allegorical images of Siena under good and bad governments (the former is better preserved than the latter). Then there are pictures showing the effect on town and countryside of good and bad government. The former are, again, better preserved than the latter).

Next time I will say a bit about Florence, including the fantastic frescoes by Domenico Ghirlandaio in the Capella Tornabuoni of Santa Maria Novella.

Thursday, 24 August 2006

One reason for continuing with the Wenlock Grand Tour, despite Mrs Wenlock's accident (she is recovering very well, and should be out of her sling in two weeks from today), was that the third part of the journey would put us in Siena at Palio time.

One reason for continuing with the Wenlock Grand Tour, despite Mrs Wenlock's accident (she is recovering very well, and should be out of her sling in two weeks from today), was that the third part of the journey would put us in Siena at Palio time.Strictly speaking, the Palio is a silk banner, as seen on the left, being paraded from the Duomo. In practice the word is used to refer to the horse race for which it is the prize. There are two races each year, on 2 July and 16 August, and Siena is packed in the days leading up to the race, despite the fact that, as an event, it makes no real concessions to non-Sienese. The Palio remains a thoroughly local event.

The race is contested in the Piazza del Campo, in the heart of the town, between horses representing ten of the city's seventeen contrade, or districts. In the days before the race itself practice races are run, and it is not uncommon to run into the horse of one or other contrada at the front of a passionate, chanting crowd of its contradaioli, on the way to or from one of these races. On the right is Zodiach, wearing the colours of Nicchio, the Noble Contrada of the Shell. I will say more of the race in another post.

The race is contested in the Piazza del Campo, in the heart of the town, between horses representing ten of the city's seventeen contrade, or districts. In the days before the race itself practice races are run, and it is not uncommon to run into the horse of one or other contrada at the front of a passionate, chanting crowd of its contradaioli, on the way to or from one of these races. On the right is Zodiach, wearing the colours of Nicchio, the Noble Contrada of the Shell. I will say more of the race in another post. The contrade are far more than supporters of a particular team in a horse race. They play a role in almost all the major rites of passage of every Sienese life, from a second baptism in your native contrada's fountain (the Wenlock Heir is shown here beside the fountain of Pantera, the Contrada of the Leopard), through education - summer camps for the youth of the contrada, for instance, marriage - almost invariably in the contrada's own Church, and support, both social and financial, in old age.

The contrade are far more than supporters of a particular team in a horse race. They play a role in almost all the major rites of passage of every Sienese life, from a second baptism in your native contrada's fountain (the Wenlock Heir is shown here beside the fountain of Pantera, the Contrada of the Leopard), through education - summer camps for the youth of the contrada, for instance, marriage - almost invariably in the contrada's own Church, and support, both social and financial, in old age. The territories of the different contrade are marked out on building walls, so that you can always tell in whose patch you are walking. In this case we are in the territory of Bruco, the Noble Contrada of the Caterpillar. The contrade are often given credit for the remarkably low levels of crime in Siena. However some (but by no means all) of the contrade have historic rivalries with each other - Pantera and Aquila, the Noble Contrada of the Eagle, for instance. In the build-up to the race, these rivalries can turn into street fights among small gangs of contrada youths. It is therefore sensible to be conscious of the risks of wearing the yellow and turquoise of Tartuca, the Contrada of the Turtle, when wandering the streets of Chiocciola, the Contrada of the Snail. Little street markers help.

The territories of the different contrade are marked out on building walls, so that you can always tell in whose patch you are walking. In this case we are in the territory of Bruco, the Noble Contrada of the Caterpillar. The contrade are often given credit for the remarkably low levels of crime in Siena. However some (but by no means all) of the contrade have historic rivalries with each other - Pantera and Aquila, the Noble Contrada of the Eagle, for instance. In the build-up to the race, these rivalries can turn into street fights among small gangs of contrada youths. It is therefore sensible to be conscious of the risks of wearing the yellow and turquoise of Tartuca, the Contrada of the Turtle, when wandering the streets of Chiocciola, the Contrada of the Snail. Little street markers help. But in Palio time the street markers are supplemented by the banners that fly from every building, and run down every street. The two banners on the left mark the border between Tartuca and Chiocciola, although we saw no signs of trouble as we walked by.

But in Palio time the street markers are supplemented by the banners that fly from every building, and run down every street. The two banners on the left mark the border between Tartuca and Chiocciola, although we saw no signs of trouble as we walked by.As might be expected, there is more noise and enthusiasm within the contrade who have horses running in the race than among those that do not, and the whole North-Eastern corner of town was a quiet refuge from the crowded masses, with Istrice, Lupa, Giraffa, Leocorno and Civetta taking no part, and of the competing contrade only Bruco amongst them.

It is not only the banners that brighten up Siena in Palio time. Frequently we heard the sound of drumming coming down the streets, signalling the passage of a procession of contrada heralds heading to or from one or other of the pre-Palio ceremonies. Here the banners of Oca, the Noble Contrada of the Goose, and Valdemontone, the Contrada of the Ram.

It is not only the banners that brighten up Siena in Palio time. Frequently we heard the sound of drumming coming down the streets, signalling the passage of a procession of contrada heralds heading to or from one or other of the pre-Palio ceremonies. Here the banners of Oca, the Noble Contrada of the Goose, and Valdemontone, the Contrada of the Ram.All seventeen contrade carry their stemme, or banners, in these parades, and indeed on the day of the race there are even representatives of six other contrade, Gallo (the Chicken), Leone (the Lion), Orso (the Bear), Quercia (the Oak Tree), Spadaforte (the Broadsword) and Vipera (the Snake) that no longer exist, following the decree of 1729 which set down the present boundaries.

The Palio is not some folkloric pageant. It has been in continuing existence since the Thirteenth Century, and while it has evolved in many ways (the current contrada heraldry is 19th Century, as the Royal insignia of the Savoy King Umberto on many of the stemme attests). I cannot claim to have understood much of what we saw while we were in Siena, but I found it fascinating. I am glad that we were there for it, and I look forward to going back some day, with a deeper understanding of how Siena works, to appreciate another Palio. I do know, however, that I will never be able to be properly part of it, as I am not Sienese. But that, I think, is one of the Palio's great strengths.

Tuesday, 22 August 2006

Most people, looking for the remains of the Empire in Rome, head for the Flavian Amphitheatre and the Forum. Queuing for ages in the former, and surrounded by crowds of fellow visitors in the latter, it is frankly impossible really to imagine what life was like when these places were in use. In any case, all you see are the remains of public buildings - mostly temples and triumphal arches.

The site of Ostia Antica, a 20-minute train ride away (1€ single fare) provides a huge contrast.

There are temples and baths here, of course (rather a lot of baths). There is a theatre too. But there are also ordinary houses, and taverns and snack bars. And they are very well preserved.

Young Wenlock was particularly taken by this caupona by the Marine Gate (towards the top left of the aerial view. Like many of the buildings in Ostia (but like few Imperial Roman buildings anywhere else) the Caupona of Alexander and Helix has intact walls and a ceiling. It dates from the early 3rd Century AD, and standing inside it one can almost imagine what it was like in its heyday - not unlike some contemporary Italian drinking establishments, I suspect.

Young Wenlock was particularly taken by this caupona by the Marine Gate (towards the top left of the aerial view. Like many of the buildings in Ostia (but like few Imperial Roman buildings anywhere else) the Caupona of Alexander and Helix has intact walls and a ceiling. It dates from the early 3rd Century AD, and standing inside it one can almost imagine what it was like in its heyday - not unlike some contemporary Italian drinking establishments, I suspect.

The theatre at Ostia ("not as big as the one at Caerleon," according to Young Wenlock, who went there on a school visit) has been restored somewhat, and is used for dramatic productions. Behind the theatre lies the Forum of the Corporations (the tree-filled area just to the right of the theatre in the aerial view). This is a wonderful place. It was, apparently, where one would go to find somebody to transport goods. It consisted of an open square with a collonade or cloister around it. The cloister had a mosaic floor, and each patch of mosaic reflected the goods that the shipper, whose little office was behind that part of the cloister, dealt in, or the part of the world with which they traded.

The theatre at Ostia ("not as big as the one at Caerleon," according to Young Wenlock, who went there on a school visit) has been restored somewhat, and is used for dramatic productions. Behind the theatre lies the Forum of the Corporations (the tree-filled area just to the right of the theatre in the aerial view). This is a wonderful place. It was, apparently, where one would go to find somebody to transport goods. It consisted of an open square with a collonade or cloister around it. The cloister had a mosaic floor, and each patch of mosaic reflected the goods that the shipper, whose little office was behind that part of the cloister, dealt in, or the part of the world with which they traded.

Apparently the "MC" on the amphora in the picture has been interpreted as meaning that this was the office of traders from Mauretania Caesariensis (modern Algeria). Whether the fish signify that they dealt specifically in fish products, I do not know. Since the staple ingredient of all Roman dishes is

Apparently the "MC" on the amphora in the picture has been interpreted as meaning that this was the office of traders from Mauretania Caesariensis (modern Algeria). Whether the fish signify that they dealt specifically in fish products, I do not know. Since the staple ingredient of all Roman dishes is dormice garum, a fermented fish sauce, this would certainly be possible. Perhaps MC salsamentum was the HP Sauce of its day.

The barely legible inscription above this creature reads STAT SABRATENSIVM. Sabrata is modern Libya, and this is suggested to be a dealer in wild animals or ivory products from there. There is a second elephant mosaic, but the beast is the wrong way up for good photography. He may well have been advertising wild animals from Egypt.

The barely legible inscription above this creature reads STAT SABRATENSIVM. Sabrata is modern Libya, and this is suggested to be a dealer in wild animals or ivory products from there. There is a second elephant mosaic, but the beast is the wrong way up for good photography. He may well have been advertising wild animals from Egypt.

I didn't take as many photographs as I might have done, given the need to keep an eye on the Wenlock Heir, so I cannot show you the apartment blocks, the mausolea, the comfortable houses with frescoed walls still in place, the several other baths with spectacular mosaics which it was quite possible to walk on, or the public toilets. All I can do is recommend that if you are interested in Roman ruins, this is better than the Forum in Rome, and possibly better than Pompeii. It is certainly less crowded. Once you get past the theatre and the baths of Neptune next door, the site seems almost deserted, even in the middle of summer.

The site of Ostia Antica, a 20-minute train ride away (1€ single fare) provides a huge contrast.

There are temples and baths here, of course (rather a lot of baths). There is a theatre too. But there are also ordinary houses, and taverns and snack bars. And they are very well preserved.

Young Wenlock was particularly taken by this caupona by the Marine Gate (towards the top left of the aerial view. Like many of the buildings in Ostia (but like few Imperial Roman buildings anywhere else) the Caupona of Alexander and Helix has intact walls and a ceiling. It dates from the early 3rd Century AD, and standing inside it one can almost imagine what it was like in its heyday - not unlike some contemporary Italian drinking establishments, I suspect.

Young Wenlock was particularly taken by this caupona by the Marine Gate (towards the top left of the aerial view. Like many of the buildings in Ostia (but like few Imperial Roman buildings anywhere else) the Caupona of Alexander and Helix has intact walls and a ceiling. It dates from the early 3rd Century AD, and standing inside it one can almost imagine what it was like in its heyday - not unlike some contemporary Italian drinking establishments, I suspect. The theatre at Ostia ("not as big as the one at Caerleon," according to Young Wenlock, who went there on a school visit) has been restored somewhat, and is used for dramatic productions. Behind the theatre lies the Forum of the Corporations (the tree-filled area just to the right of the theatre in the aerial view). This is a wonderful place. It was, apparently, where one would go to find somebody to transport goods. It consisted of an open square with a collonade or cloister around it. The cloister had a mosaic floor, and each patch of mosaic reflected the goods that the shipper, whose little office was behind that part of the cloister, dealt in, or the part of the world with which they traded.

The theatre at Ostia ("not as big as the one at Caerleon," according to Young Wenlock, who went there on a school visit) has been restored somewhat, and is used for dramatic productions. Behind the theatre lies the Forum of the Corporations (the tree-filled area just to the right of the theatre in the aerial view). This is a wonderful place. It was, apparently, where one would go to find somebody to transport goods. It consisted of an open square with a collonade or cloister around it. The cloister had a mosaic floor, and each patch of mosaic reflected the goods that the shipper, whose little office was behind that part of the cloister, dealt in, or the part of the world with which they traded. Apparently the "MC" on the amphora in the picture has been interpreted as meaning that this was the office of traders from Mauretania Caesariensis (modern Algeria). Whether the fish signify that they dealt specifically in fish products, I do not know. Since the staple ingredient of all Roman dishes is

Apparently the "MC" on the amphora in the picture has been interpreted as meaning that this was the office of traders from Mauretania Caesariensis (modern Algeria). Whether the fish signify that they dealt specifically in fish products, I do not know. Since the staple ingredient of all Roman dishes is  The barely legible inscription above this creature reads STAT SABRATENSIVM. Sabrata is modern Libya, and this is suggested to be a dealer in wild animals or ivory products from there. There is a second elephant mosaic, but the beast is the wrong way up for good photography. He may well have been advertising wild animals from Egypt.

The barely legible inscription above this creature reads STAT SABRATENSIVM. Sabrata is modern Libya, and this is suggested to be a dealer in wild animals or ivory products from there. There is a second elephant mosaic, but the beast is the wrong way up for good photography. He may well have been advertising wild animals from Egypt.I didn't take as many photographs as I might have done, given the need to keep an eye on the Wenlock Heir, so I cannot show you the apartment blocks, the mausolea, the comfortable houses with frescoed walls still in place, the several other baths with spectacular mosaics which it was quite possible to walk on, or the public toilets. All I can do is recommend that if you are interested in Roman ruins, this is better than the Forum in Rome, and possibly better than Pompeii. It is certainly less crowded. Once you get past the theatre and the baths of Neptune next door, the site seems almost deserted, even in the middle of summer.

Sunday, 20 August 2006

With so much travel involved in the Grand Tour, and with the Wenlock Heir's predisposition to spend the heat of the day splashing around in swimming pools, and with such trips being, in principle, about relaxation and enjoyment, selecting the right reading matter was an important part of holiday planning in the Wenlock household. I wanted, as far as possible, books that would give me a feel for the places we were visiting: Rome, Florence and Siena. For Florence a useful starting point was Fictional Cities, which is perhaps why I did better on that city than on the other two.

The one book that covered Siena was Mary Hoffman's City of Stars. This is the second in the Stravaganza series, young adult books set in an alternative 16th Century Italy and involving visitors from 21st Century North London to a world dominated by the De Chimici family. The focus of City of Stars is a version of the Palio, Siena's famous horse race (of which much more in another post). The third book, City of Flowers, addresses an alternative Florence, and the machinations of the head of the De Chimici family, which bare considerable similarities to aspects of de Medici activities. Highly recommended.

The one book that covered Siena was Mary Hoffman's City of Stars. This is the second in the Stravaganza series, young adult books set in an alternative 16th Century Italy and involving visitors from 21st Century North London to a world dominated by the De Chimici family. The focus of City of Stars is a version of the Palio, Siena's famous horse race (of which much more in another post). The third book, City of Flowers, addresses an alternative Florence, and the machinations of the head of the De Chimici family, which bare considerable similarities to aspects of de Medici activities. Highly recommended.

Sarah Dunant's The Birth of Venus is a brilliant capturing of late 15th Century Florence, when the de Medicis were briefly eclipsed, folowing the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent, by both the invading armies of the Holy Roman Emperor and by the fanatical preaching of Giralamo Savonarola. She captures the growing menace of Savonarola's rabble rousing, the approaching French army, and the threat of plague brilliantly, entwining it around a brilliantly characterised heroine. I found this book a real page-turner, but one that was also deeply satisfying to look back upon; a rare combination.

Sarah Dunant's The Birth of Venus is a brilliant capturing of late 15th Century Florence, when the de Medicis were briefly eclipsed, folowing the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent, by both the invading armies of the Holy Roman Emperor and by the fanatical preaching of Giralamo Savonarola. She captures the growing menace of Savonarola's rabble rousing, the approaching French army, and the threat of plague brilliantly, entwining it around a brilliantly characterised heroine. I found this book a real page-turner, but one that was also deeply satisfying to look back upon; a rare combination.

Mark, at Mostly Books, suggested Umberto Eco's The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, although it is not set in Rome, Florence or Siena. I have read and enjoyed all of Eco's earlier novels (of which Baudolino might have been the most relevant to this trip) and had planned to read this one at some point anyway, so Mark did not need to nudge me very hard. Like all of Eco's books it contains plenty of philosophical speculation, on identity and memory in particular. The protagonist is a man who has lost his memory of his own life, but not of all the facts that he has learned through the years. Eco uses this device, among other things, to explore the Italian national psyche during the Second World War, and how this was reflected in popular culture - comic books, popular music and so on. If this makes it all sound very dry, it shouldn't do. It was a wonderful book and, unusually for a novel, it is richly illustrated with examples of the popular culture which it discusses. I learned a great deal from it about Italy in the second quarter of the last Century.

Mark, at Mostly Books, suggested Umberto Eco's The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, although it is not set in Rome, Florence or Siena. I have read and enjoyed all of Eco's earlier novels (of which Baudolino might have been the most relevant to this trip) and had planned to read this one at some point anyway, so Mark did not need to nudge me very hard. Like all of Eco's books it contains plenty of philosophical speculation, on identity and memory in particular. The protagonist is a man who has lost his memory of his own life, but not of all the facts that he has learned through the years. Eco uses this device, among other things, to explore the Italian national psyche during the Second World War, and how this was reflected in popular culture - comic books, popular music and so on. If this makes it all sound very dry, it shouldn't do. It was a wonderful book and, unusually for a novel, it is richly illustrated with examples of the popular culture which it discusses. I learned a great deal from it about Italy in the second quarter of the last Century.

I picked Christobel Kent's story of goings on among the English expat community in Florence, A Party in San Niccolo, from the review on Fictional Cities and I was not disappointed. As the review makes clear this is a book that contains murder and mystery without being a murder mystery. It helped give me a feel for Florence before we arrived, but the story takes place in the spring, when the streets of town are not packed with tourists, whose activities rather drown out any sense of what the city is like to live in year-round.

I picked Christobel Kent's story of goings on among the English expat community in Florence, A Party in San Niccolo, from the review on Fictional Cities and I was not disappointed. As the review makes clear this is a book that contains murder and mystery without being a murder mystery. It helped give me a feel for Florence before we arrived, but the story takes place in the spring, when the streets of town are not packed with tourists, whose activities rather drown out any sense of what the city is like to live in year-round.

Judy Astley's Blowing It was a complete break from Italy, but was just the sort of book to read while dealing long-distance with insurance companies and others while sorting out Mrs Wenlock's emergency flight home. Judy claims that it is not one of her best, but it is still a well-constructed tale of a slightly unconventional family almost falling apart and eventually sorting themselves out. The central character, Lottie, is married to the former lead singer of a 70s soft rock band (Charisma, described as a cross between Fairport Convention and Fleetwood Mac, which I still struggle to imagine). Their philosophy of life tends to involve throwing themselves into new ventures without much thought for the consequences, and with the income from Charisma's back catalogue falling their latest plan, to have a "gap year" themselves, now that their youngest child is about to do the same before University, involves selling the huge but crumbling family home, to the horror of their somewhat conventional children.

Judy Astley's Blowing It was a complete break from Italy, but was just the sort of book to read while dealing long-distance with insurance companies and others while sorting out Mrs Wenlock's emergency flight home. Judy claims that it is not one of her best, but it is still a well-constructed tale of a slightly unconventional family almost falling apart and eventually sorting themselves out. The central character, Lottie, is married to the former lead singer of a 70s soft rock band (Charisma, described as a cross between Fairport Convention and Fleetwood Mac, which I still struggle to imagine). Their philosophy of life tends to involve throwing themselves into new ventures without much thought for the consequences, and with the income from Charisma's back catalogue falling their latest plan, to have a "gap year" themselves, now that their youngest child is about to do the same before University, involves selling the huge but crumbling family home, to the horror of their somewhat conventional children.

I found Emma Tennant's Felony in the BM Bookstore in Florence. It has to count as liteary fiction on many levels. It tells of Claire Clairmont's last days in the late 19th Century. Clairmont was a friend and lover of Byron and Shelley, and was with them at the Villa Diodati near Geneva when Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein and John Polidori wrote The Vampyre. In her eighties she lived in Florence where she was preyed upon by an American sea captain with a Shelley obsession who hoped to inherit her papers when she died. This (true) story was the inspiration for Henry James' The Aspern Papers, and Tennant weaves an account of James researching and writing that book in the 1880s with Clairmont's woes in the 1870s. Interesting, if not quite as gripping as Dunant's story.

I found Emma Tennant's Felony in the BM Bookstore in Florence. It has to count as liteary fiction on many levels. It tells of Claire Clairmont's last days in the late 19th Century. Clairmont was a friend and lover of Byron and Shelley, and was with them at the Villa Diodati near Geneva when Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein and John Polidori wrote The Vampyre. In her eighties she lived in Florence where she was preyed upon by an American sea captain with a Shelley obsession who hoped to inherit her papers when she died. This (true) story was the inspiration for Henry James' The Aspern Papers, and Tennant weaves an account of James researching and writing that book in the 1880s with Clairmont's woes in the 1870s. Interesting, if not quite as gripping as Dunant's story.

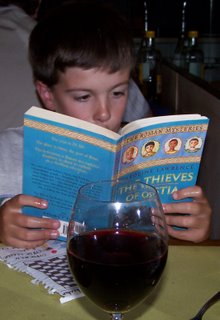

Meanwhile the Wenlock Heir, having visited the site of Ostia Antica, spent his free hours devouring the series of Roman Mysteries written by Caroline Lawrence. He found these so gripping that he would bring them along to restaurants, and at times would choose reading over splashing about in the pool. He worked his way through five of the series and would have read more if I could have found them in the local shops.

Meanwhile the Wenlock Heir, having visited the site of Ostia Antica, spent his free hours devouring the series of Roman Mysteries written by Caroline Lawrence. He found these so gripping that he would bring them along to restaurants, and at times would choose reading over splashing about in the pool. He worked his way through five of the series and would have read more if I could have found them in the local shops.

The one book that covered Siena was Mary Hoffman's City of Stars. This is the second in the Stravaganza series, young adult books set in an alternative 16th Century Italy and involving visitors from 21st Century North London to a world dominated by the De Chimici family. The focus of City of Stars is a version of the Palio, Siena's famous horse race (of which much more in another post). The third book, City of Flowers, addresses an alternative Florence, and the machinations of the head of the De Chimici family, which bare considerable similarities to aspects of de Medici activities. Highly recommended.

The one book that covered Siena was Mary Hoffman's City of Stars. This is the second in the Stravaganza series, young adult books set in an alternative 16th Century Italy and involving visitors from 21st Century North London to a world dominated by the De Chimici family. The focus of City of Stars is a version of the Palio, Siena's famous horse race (of which much more in another post). The third book, City of Flowers, addresses an alternative Florence, and the machinations of the head of the De Chimici family, which bare considerable similarities to aspects of de Medici activities. Highly recommended. Sarah Dunant's The Birth of Venus is a brilliant capturing of late 15th Century Florence, when the de Medicis were briefly eclipsed, folowing the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent, by both the invading armies of the Holy Roman Emperor and by the fanatical preaching of Giralamo Savonarola. She captures the growing menace of Savonarola's rabble rousing, the approaching French army, and the threat of plague brilliantly, entwining it around a brilliantly characterised heroine. I found this book a real page-turner, but one that was also deeply satisfying to look back upon; a rare combination.

Sarah Dunant's The Birth of Venus is a brilliant capturing of late 15th Century Florence, when the de Medicis were briefly eclipsed, folowing the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent, by both the invading armies of the Holy Roman Emperor and by the fanatical preaching of Giralamo Savonarola. She captures the growing menace of Savonarola's rabble rousing, the approaching French army, and the threat of plague brilliantly, entwining it around a brilliantly characterised heroine. I found this book a real page-turner, but one that was also deeply satisfying to look back upon; a rare combination. Mark, at Mostly Books, suggested Umberto Eco's The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, although it is not set in Rome, Florence or Siena. I have read and enjoyed all of Eco's earlier novels (of which Baudolino might have been the most relevant to this trip) and had planned to read this one at some point anyway, so Mark did not need to nudge me very hard. Like all of Eco's books it contains plenty of philosophical speculation, on identity and memory in particular. The protagonist is a man who has lost his memory of his own life, but not of all the facts that he has learned through the years. Eco uses this device, among other things, to explore the Italian national psyche during the Second World War, and how this was reflected in popular culture - comic books, popular music and so on. If this makes it all sound very dry, it shouldn't do. It was a wonderful book and, unusually for a novel, it is richly illustrated with examples of the popular culture which it discusses. I learned a great deal from it about Italy in the second quarter of the last Century.

Mark, at Mostly Books, suggested Umberto Eco's The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, although it is not set in Rome, Florence or Siena. I have read and enjoyed all of Eco's earlier novels (of which Baudolino might have been the most relevant to this trip) and had planned to read this one at some point anyway, so Mark did not need to nudge me very hard. Like all of Eco's books it contains plenty of philosophical speculation, on identity and memory in particular. The protagonist is a man who has lost his memory of his own life, but not of all the facts that he has learned through the years. Eco uses this device, among other things, to explore the Italian national psyche during the Second World War, and how this was reflected in popular culture - comic books, popular music and so on. If this makes it all sound very dry, it shouldn't do. It was a wonderful book and, unusually for a novel, it is richly illustrated with examples of the popular culture which it discusses. I learned a great deal from it about Italy in the second quarter of the last Century. I picked Christobel Kent's story of goings on among the English expat community in Florence, A Party in San Niccolo, from the review on Fictional Cities and I was not disappointed. As the review makes clear this is a book that contains murder and mystery without being a murder mystery. It helped give me a feel for Florence before we arrived, but the story takes place in the spring, when the streets of town are not packed with tourists, whose activities rather drown out any sense of what the city is like to live in year-round.